Dancing in my sleep: a story of gruesome and popular entertainment during Great Depression

Dance marathons have been described as the reality TV shows of the 1920s and 1930s. Originating in the United States and wildly popular in the 1920s and 30s, these dance endurance competitions took place before paying audiences and, unbelievably, could last for weeks or even months on end. Why on earth did people take part in this protracted form of torture, and why did they have such gruesome appeal?

The ultimate competition, dancing for months on end

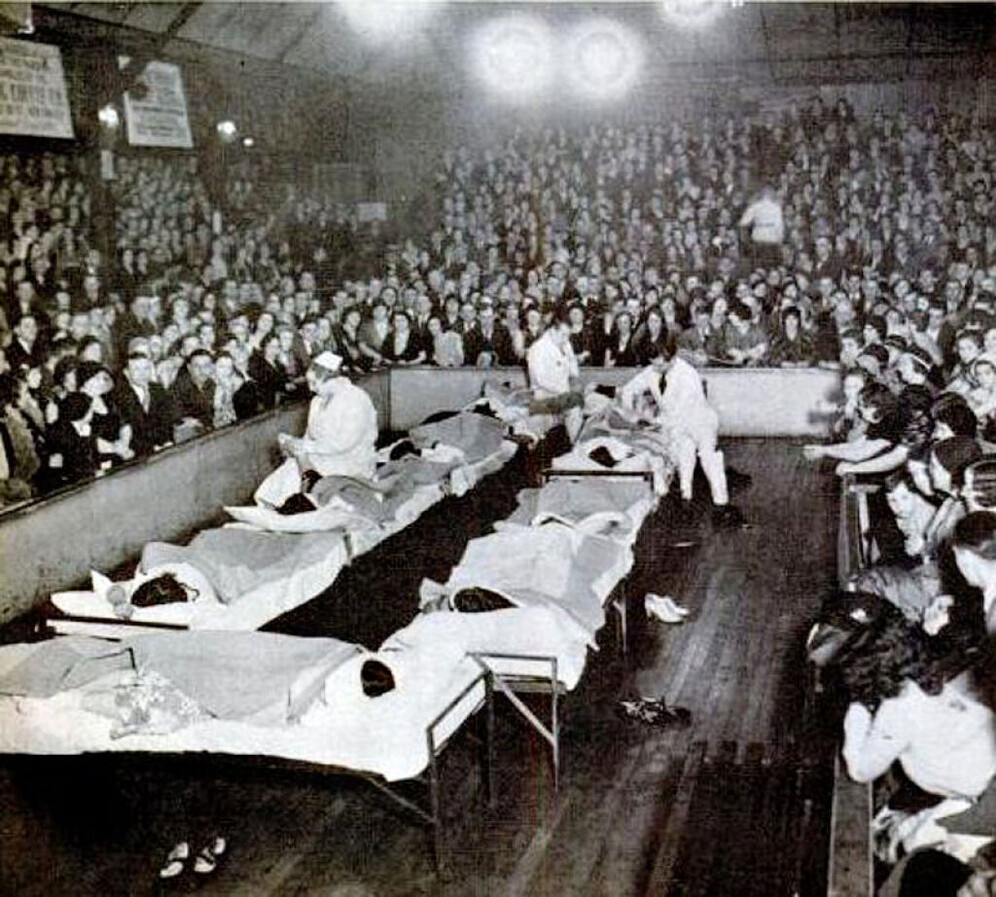

Dance marathons were competitions between pairs of dancers to see who could dance the longest, for cash prizes. They took place in ballrooms, gyms and other entertainment venues. The contestants circled the dance floor surrounded by stands for the audience.

The craze started in 1923 when a woman named Alma Cummings danced for a record-breaking 27 hours with six different partners, but her record kept on getting broken, and they soon developed into shows that could last for much longer. The Dance Derby of a Century, which took place in New York's Madison State Garden, stretched from 10 to 30 June 1928. In 1935, Anita O'Day, a teenager, danced with her partner "for 97 days, covering 4,656 miles in 2,328 hours. They came second", according to the Guardian.

Dancers were entitled to 15-minute breaks after 45 minutes or an hour of dancing when they could sleep in cots on the dance floor, attended by nurses, masseurs and chiropodists. They often ate or shaved while dancing, and one partner slept while the other dragged them along.

Rules, enforced by floor judges, required that contestants keep moving their feet. If their knees touched the floor while they were slumped from exhaustion, they were eliminated.

The 1920s dance marathon craze

The first dance marathon is said to have taken place in 1910 in two parts, the second of which lasted for fifteen hours.

However, the craze took off in the 1920s. At the time, endurance competitions of all sorts, including "kissing marathons" were all the rage. The decade was also the golden age of ballroom dancing, so it was unsurprising when the two trends merged. Promoters saw their chance to turn a fad into profitable show business, by enhancing the formula to create addictive appeal.

So, what compelled audiences to pay for what was very far from exhibition dancing? One reporter at the New York World described an early dance marathon as a rather bleak spectacle:

"A dingy hall is littered with worn slippers, cigarette stubs, newspapers and soup cans; reeking with the odour of stale coffee, tobacco smoke, chewing gum and smelling salts. Girls in worn bathrobes, dingy white stockings, their arms hanging over their partners' shoulders, dragging their aching feet in one short agonising step after another", as quoted in Literary Digest 5 May 1923.

Dance marathons attracted a majority of women to the audience. Apparently, they felt a mixture of glee and motherly compassion at the sight of others dragging themselves around a dance floor to save energy.

Promoters encouraged drama and created conflict between couples with different personas, the wholesome "sweetheart couple" the majority rooted for, or the "trouble maker" baddies. The trick was to get audience members to identify with a favourite and get invested in their fortunes.

To mix things up and bring the competition to a conclusion before audiences lost interest and stopped coming, putting them out of pocket, promoters could also change the rules as they went along, for instance reducing rest times, or imposing dance numbers to tire competitors out.

-8-br.jpg)

The use of vaudeville acts, such as "smile" popularity features, with one Derby of a Century winner Mary Promitis, initially "over-smiling" in the first three-minute contest, before winning the next four others. Promoters could also hire ballroom dancing teams to cut up the dance floor with proper exhibitions of the foxtrot or the two-step for prize money. In short, whatever the time of day, something was going on, or might be.

However, "the main attraction of the show continued to be the surviving contestants struggling to keep each other in an upright position after walking forty miles a day[...] They slapped faces, punched jaws and kicked in the shins. Such acts were greeted with cheers from the 'sporting element', spectators who wagered which team would hold up longest under such abuse", explains Frank M. Calabria in Dance of the Sleepwalkers, the Dance Marathon Fad.

Like present-day reality TV, it is unclear how much of the drama was staged. For instance, the Derby of the Century was finally closed down by New York City police, and the prize remained unawarded. Still, some suspect that the promoter was in on this, and the intervention was a way to infuse drama and avoid expenses to keep his show profitable.

The contestants were attracted by the prize money, which could be substantial. Companies also sponsored teams, providing them with kit, which they got to keep regardless of the outcome. Although the Roaring Twenties were a time of consumerism, unemployment was already a problem, and so there was no shortage of takers for the dance marathons.

A dark turn in the 1930s

The dark reputation of dance marathons today mostly comes from Horace McCoy's novel They Shoot Horses Don't They? which was made into a highly acclaimed film directed by Sydney Pollack and starring Jane Fonda in 1969.

The novel starts with a murder scene, where Rob, a dance marathon contestant shoots his partner Gloria to put her out of her misery, like a fallen race-horse, after enduring months of misery dragging themselves around a California dance floor during the Great Depression.

The Depression changed audiences and contestants. With a quarter of the US' working population out of work, cheap entertainment for the newly idle was a welcome relief, as was the sight of those worse off than themselves "They just want to see a little misery out there so they can feel a little better maybe. They're entitled to that", in the words of one of Horace McCoy's characters.

For the contestants, the prize money proved tantalising. More than that, while they were competing, they were well-fed and had a roof over their heads for as long as they could stay standing. Unemployed actors, such as Gloria and Rob, hoped to get noticed, reviving their careers.

The walkathons, as they began to be known, also fed a psychological need. "In the early 1930s, a good number of teams who competed in walkathon shows were unemployed. The need to survive was not the only urgent reason. Contestants often felt uprooted and unwanted, a lost generation. Joining a walkathon show was finding a home of sorts" , according to Frank M. Calabria

The competitions lasted longer and longer. Walkathons, where couples simply had to keep walking in a circle, made things even physically tougher. Promoters also had agreements with professional contestants that toured from city to city, pitting themselves against local amateurs, rigging the outcome even more.

Real and imagined dangers

From the start, dance marathons attracted criticism of the grounds of health and morality. Many felt taking pleasure from someone else's misery was an unacceptable form of entertainment. Thus certain cities such as Boston banned the format.

Churches and women's groups were concerned about the dangers to which young women were exposed by the sexually charged activity of dancing.

Tales of a young woman being committed to a mental institution after a few days of dancing, as well as the hallucinations that dancers often suffered from, drew indignation.

In 1923, a 27-year-old man, Horace Morehouse, collapsed and died on the dance floor after dancing for 87 hours.

Such tragedies were the exception, however. Thirties promoter Leo Seltzer tried to prove the activity was healthy. He roped in a doctor to establish 80% of contestants were in better shape after taking part in a dance marathon than beforehand.

Whatever the case may be, the craze established that human beings are far more enduring than might be expected.

Decline and fall

Dance marathons continued to take place until the early 1950s, but several factors explain their decline after the end of the Great Depression. Unemployment went down, so contestants had other options. The start of World War II meant they could get jobs in industry, as the United States economy roared into life to produce the weapons needed for the Allies' war effort, or they could enlist to fight. Thus contestants started asking for better pay and conditions, eating into promoters' profits.

Also, by the early 1950s, half of US states had banned such endurance contests, and in other states, cities often took out local ordinances against them, reducing possibilities. The advent of television in the 1950s provided alternative cheap mass family entertainment, killing the shows dead.