‘Notes from the Underground’: Dostoevsky and the Black Lives Matter Movement

The world has recently celebrated the 200th anniversary of the birth of Fyodor Dostoevsky. A famous writer in Russia, he remains among the five most popular globally. The never-ending relevance of his books has secured Dostoevsky a prominent place in cultural heritage and continues to raise avid interest in readers all over the globe. Though written so many years ago, Dostoevsky’s pieces accurately reflect many of the major ills of modern society and people. Among those who find inspiration in Dostoevsky’s characters are black American activists fighting for empowerment. Tune in to the premiere of Universal Dostoevsky tomorrow to learn more!

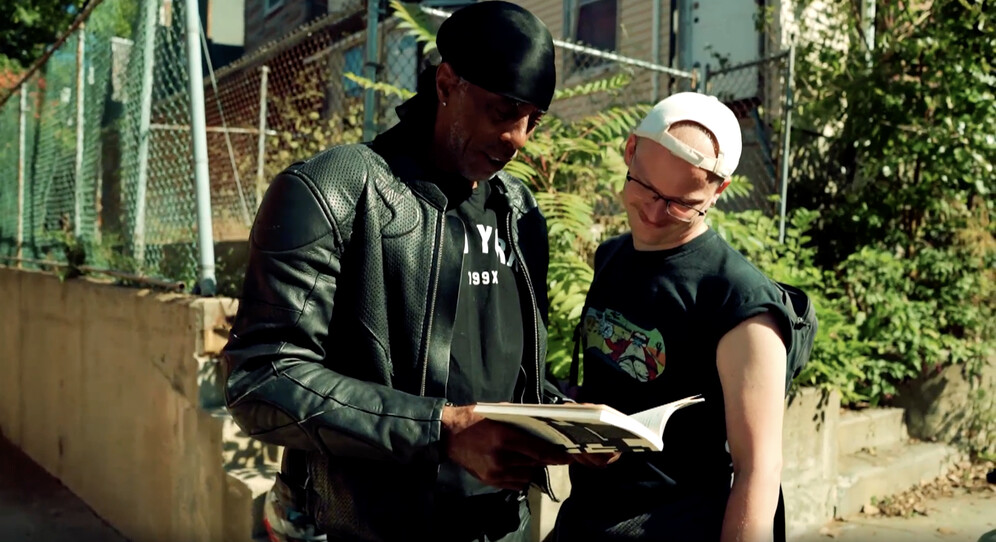

Philadelphia, USA. A black actor is practising the part of the main character from Dostoevsky’s ‘Notes from the Underground’ for an online play. However, the plot is not the same as the Russian writer initially conceived it. Instead, it’s been adapted to the realities of today’s America.

In the online play, the lead character is not a retired government official from Saint Petersburg, as Dostoevsky wrote, but a black police officer who has worked too long for a system steeped in violence and racism.

The image of an oppressed man in ‘Notes from the Underground’ has become particularly relevant to a new generation of black Americans fighting for their rights: the concept of a hero isolated from the outside world and fighting an internal battle came in the wake of the pandemic.

“We wanted to do a whole season of shows around isolation to match our moment of being in isolation due to COVID,” says Dane Eissler, director of the play. “And to reflect the time that we’re going through. And this is kind of a cool thing about this adaptation — you’re just overlaying those different given circumstances, like, ‘Okay, no more 19th century, it’s the 21st century.’ I was like, ‘Oh, wow! This is really easy to recontextualise.’ Yeah. And they talk about politics, how, like… a man’s perspective, and how he treats a woman.”

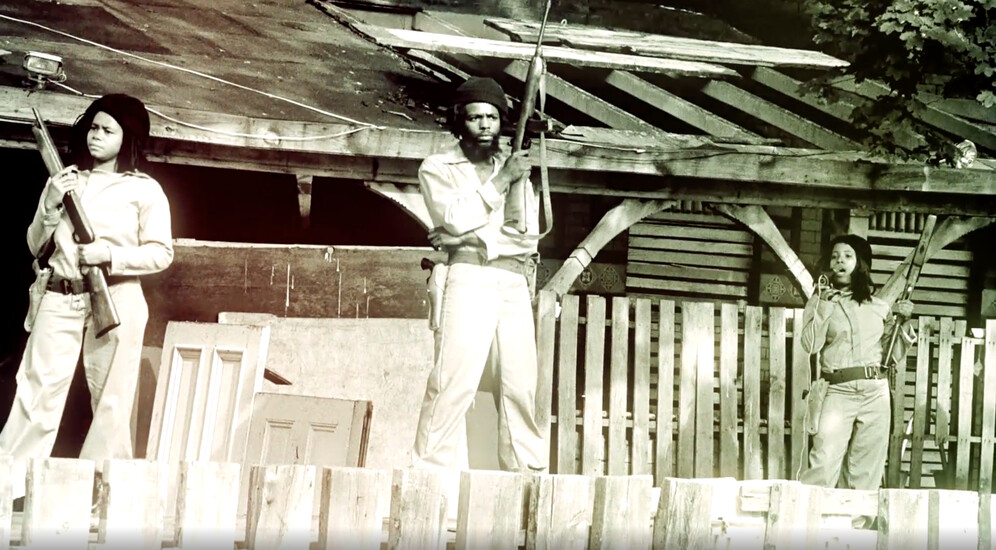

The story was inspired by events here, in Philadelphia, in May 1985. Police killed eleven people and destroyed a residential block when bombing activists from MOVE. The Philadephia-based organisation advocated natural living, opposed technological progress, and campaigned for animal rights.

The events of 1985 pushed the main character of Dane Eissler’s play to go underground. However, he resurfaced in the new age of protest and met Liza. In Dostoevsky’s version, she was a prostitute, and in Eissler’s interpretation – an activist advocating Black American empowerment.

MOVE was a real nuisance to the US authorities. The black hippies opposed the political and social system based on white supremacy. In an attempt to make their case, they regularly disrupted local government proceedings, sheltered drug addicts, and eventually took up arms to defend their convictions.

The state classified the group as a terrorist organisation and finally decided to be eliminated by military means. However, the operation against MOVE ended in a tragedy – a residential area was bombed, and the resulting fire destroyed dozens of houses.

Circumstances change. The form of struggle of modern African-American activists is different from that of Dostoevsky’s character. But the nature of the inner personal struggle doesn’t change over the centuries.

“I mean, both pieces are kind of a protest piece,” says Dane Eissler. “Like, Dostoevsky was kind of commenting on the Russia of his time. In our piece, we’re commenting on the Philadelphia and the United States of our time.”

People often turn to Dostoevsky’s pieces to understand Russia and Russians. But after reading them, they end up with a better understanding of themselves.

Fyodor Dostoevsky’s unique ability to decrypt human nature and transform the reader is the unshakable foundation of his lasting worldwide popularity. Dostoevsky continues to be read and understood on all continents, with Dane Eissler’s play far from the only modern interpretation of his pieces.

“To me, Dostoevsky is the man with a strong character. Despite all the difficulties, he managed to start over, get back to work and, surely, give life a deep meaning through his novels. In my opinion, Russians have that strength of character and determination that allowed this person — after everything he’d been through — to create the great novel, which we don’t just read 200 years later, but learn from it.”

In the US, North Carolina is one of the major academic centres for Dostoevsky studies. The leading state universities hold an annual ‘Dostoevsky Games’ – a contest for students interested in the Russian writer and eager to develop a new interpretation of his ideas. The interpretations vary, from abstract paintings to rap, but the ideas they are based on remain practically intact.

“He always says, all of his characters say, Stavrogin or Pyotr Stepanovich, or Shatov, or Sonya in Crime and Punishment… ‘Beg forgiveness! That’s what you have to do. You can be saved. You can better yourself. You can be improved.’”

“We do this because we think people are either undeserving or incapable of rehabilitation. They’ve done something bad, and now they can be thrown away like human trash, and Dostoevsky says, That’s not true! Even the murderer Raskolnikov can be sent away to prison. He can read his Bible. He can be saved by Sonya, and he can be better. Dostoevsky was a witness to that himself.”

To learn more about modern interpretations of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s pieces worldwide, tune in to the premiere of Universal Dostoevsky tomorrow!