“We grew up playing in the woods at the back of our house” - Jane Gillis on why a forest makes the best school

Jane Gillis runs a Forest School with her brother in Bristol, in the West of England. They take children out of the classroom into nature to learn by exercising their freedom and imagination. She tells RTD what's so special about playing in the woods and how she turned childhood games into a grown-up job.

What playing in the woods can teach you

We grew up playing an awful lot in the woods at the back of our house. Forest School is just a continuation of that and sharing that love of nature with kids of all ages. It's a small business; it's just my brother and I that run it.

Generally, the youngest is about two years old, to as old as you want to go. We're on the outskirts of Bristol, but we go to all sorts of different places with children from different schools around the city.

Basically, we love being outdoors. We love learning outdoors. The whole ethos is that the children lead you, you are guided by the environment, by what's presented to you.

If you're in a classroom, you're really quite limited. You just haven't got all that stimulus. So getting outdoors, getting to some woods in particular... it's just a sensory world! We're facilitating learning, exploring and playing. We're big on play for all ages. Play is something you learn and develop through.

We do Forest School, but it's a bit broader than that as well. We'll do lots of different environments, like streams... We quite like going to a beach, we've got one or two that you can go to near Bristol. They're not amazing, but they do the job of helping you to learn to act in an environment that's different than woodland.

We also run outdoor learning activities. Everyone in Britain at a certain age, by the time they're about eight or something, has to have done this whole module on the Stone Age. It's quite hard for kids to get into it. So we do our Stone Age workshop.

My favourite is allowing the kids to do lots of imaginative play and seeing the benefits of that. Instead of saying, "This is below your years", giving them permission to get immersed in imaginative play. It could be saying "Let's make an elf world!" and just seeing their imaginations go. Then their teamwork gets developed as they do that.

How going outside changes children on the inside

I also love seeing them getting more and more in tune with an environment they're not normally tuned into. Seeing that interest growing week after week, in the plants that are growing, in the trees, in the things they're seeing because they're seeing them. Seeing the children flourishing by connecting with the natural world is brilliant.

Another thing that we love to do, if we work with them for several weeks, is letting them set the agenda for the next week and involving them in the planning. So you get a group, they're going "Oh next week can we...?"

Or it's honing their fire skills or using certain tools. I love seeing the faces of teachers when you say, "Yeah, we are actually going to use knives and we are going to let that one that you think, 'Oh, my goodness, what are you letting them use the axe for?' handle one".

For some children, a contained classroom scenario really doesn't work. They are the ones who really struggle, but then time after time you see them flourishing in an outdoor environment. Then the teachers who come out and see them go, "Oh, my goodness, that's amazing that they're reacting like that!"

For some of the children with special needs, the effect of a woodland environment can be incredibly helpful. For example, there are some children who have got emotional difficulties. Then you see them being cradled in a hammock, and the calming nature of a hammock becomes a safe place for them.

It becomes quite a focus for that week, and it becomes quite a focus for their enjoyment of coming into school. The teachers can then talk about it with them. If you have children for whom being able to say positive things about what they're doing is tricky, to be actually able to have that feedback about them having a really positive experience in school is very helpful. They take into the classroom something they've made like a mallet. They gain self-worth, and their self-esteem goes up. They've taken risks, and they've achieved stuff, and that makes them feel good about themselves. And then they can feed that back into the classroom.

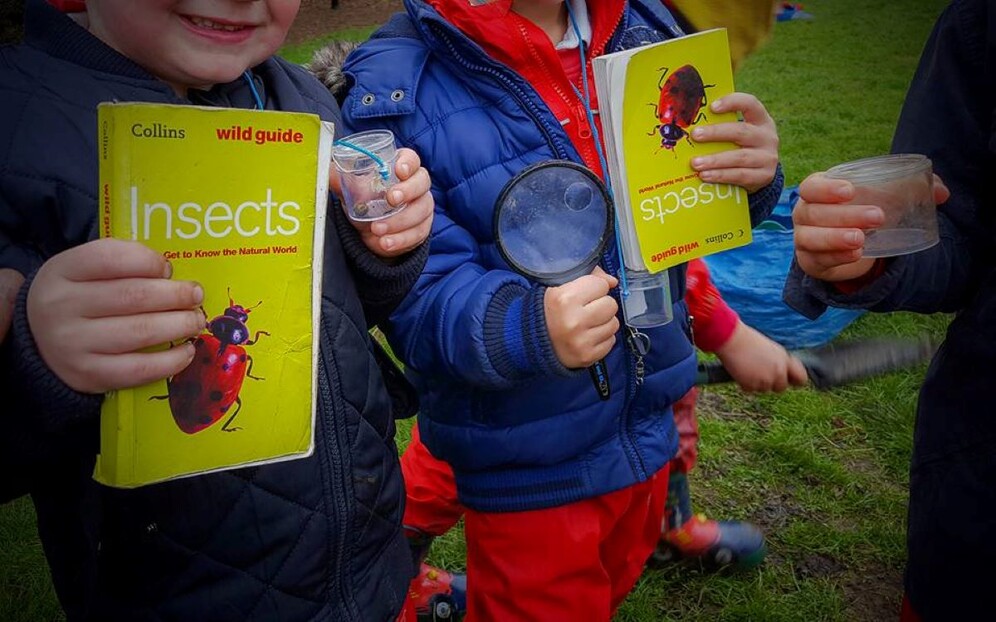

We see them in a lot of different environments, in a lot of scenarios that they wouldn't necessarily get in a small classroom. We're seeing them in in a bit more breadth, so we're able to say: "You know what, what we're seeing this, what could that lead to?" Maybe it's their ability to get on with everyone, or their interest in intriguing little creatures.

The positive impact of spending time in nature is just massive, on your wellbeing, on your learning. In the statistics for the UK, there's something called Nature Deficit Disorder, which is they're not getting enough nature. It's really variable, but in most of the kids that we spend our time with, you can see elements of Nature Deficit Disorder. They live in tower blocks and flats, and they've got no outdoor space. The only thing they've got is an urban park, and it's quite clinical nature.

We work with a preschool as well. The manager is passionate about herself and us communicating to the parents: "Take your kids outside! Don't be on some big agenda. Go with their flow." We do quite a lot of family things, to try to pass on that love of wild to the families as well, so that they make it more and more part of their lives. We generally see those families more and more embracing what they can do outdoors.

A teacher who loves school, but loves the outdoors more

How did I get to that place?

I had a lot of fun at primary school. I was at school in the eighties when teaching was quite topic-based, and teachers had a lot of freedom before the National Curriculum came in. Going up to secondary school, it varied. Some of it I loved. Some lessons, I spent a lot of time looking out of the window.

I've always loved the outdoors, and I've always loved kids, so teaching was a natural thing.

That gives you lots of skills, like the management of large groups. My brother and I both studied geography. My brother has been a primary school teacher. I've been secondary.

-20-br.jpg)

Teaching geography, I've done lots and lots of outdoor trips. Then I've done mountain leadership things, taking people out in the mountains.

I got into climbing mountains more and more in my mid-teens. I loved all of that, went climbing most weekends. Then at 23, I had a climbing accident; I broke a very unusual bone in my foot called the talus. It's really, really hard for that bone to heal properly. I think the doctor said when I saw them the day after, "You are going to walk with a stick for the rest of your life". I spent about a year recovering.

Before that accident, I wouldn't think twice about a seventeen-mile walk. Afterwards, the maximum would be eight miles, in quite a bit of pain. What changed for me is I had a bit more of a shift to helping others enjoy the outdoors.

Now I've got end-stage arthritis in my ankle. But I've got the most amazing invention ever. The only option that was being presented to me by the NHS here was fusion, an operation that fuses the whole ankle, which leads to other fusions.

It was quite a depressing scenario. I spent weeks researching options. Quite a few were doing elective amputations and were going for running blades.

Then I came across this amazing guy in America. He worked for the military. He was so fed with doing running blades for people who'd had elective amputations that he designed this brace. It's like a running blade, but you keep your leg. You switch off everything from the knee down and rely on the brace. Some people gave me the money, it's quite expensive, but it's been worth its weight in gold.

Taking risks to find your calling

After teaching, I worked for a church for a bit and did all their kids' stuff. At the church, for various reasons, we had to take voluntary redundancy. So I had six-seven months when I could ask myself "What would I love to happen next? What do I love doing?"

You try to be careful with the redundancy money, but I think you've got to spend that time. For me, God is a massive part of that. To say "OK, God, there's only ever going to be one me on planet Earth, not to big myself up, but there's only one life for this. What is it that you're calling me to, in this life?"

It's been a bit of a financial risk starting our Forest School. Thankfully, I've got the backup of Andy, my husband, who's a nurse. But even if I wasn't married to him, I think you just do it anyway. See if it works, if it doesn't, try something else.

I loved teaching. I love that connection with children. I love seeing them excited about learning. But again, I mean, geography's a bit of a win subject, you get the coloured pencils out. There's so much to grab children's attention, geography if you bring it alive. I constantly found myself with photos, with videos, just trying to bring it alive. But I always wished I could take them to a place because they'd get it. They'd see it. They feel it. They measure it.

My brother and I were getting quite frustrated with classroom environments. There's a lot of constraints. There's a lot of ways that teachers are told how children should learn and what they should learn. And it doesn't fit everyone or let children flourish. It is quite cold. You get why it is like it is because you've got one teacher, you've got thirty pupils sitting in front of you, so you're restricted in how you deliver. We were also more and more passionate about what can be done in an outdoor environment.

Forest School started in Sweden, Finland and the Scandinavian countries. Then it got going here more and more. Maybe ten years ago. We've seen quite a boom of it. Its growth has plateaued out now. Since we've started six years ago, we've got more confident. We also adapt our services to fit where the money is available.

The first week of lockdown, all our activities got cancelled. And then we got calls from schools we've worked with for a long time, asking us to do stuff with the children of key workers, and vulnerable children.

That's basically what we've done all the way through. It's been a huge privilege. We've worked with small groups, with the same kids all the way through from March, to June, July. That's let us have a really calm and really positive influence on the lives of these children. Now, we're trying to plan ahead, but you never know what happens next.

For people who want to start their own Forest School, there's lots of training material available. I would say. Just check that you're up for it in the rain. It goes on and on and on. In the wet and the mud. Can you still have a passion for it if it's raining? Because that's the reality, particularly in Britain.