Euro-Burma Office head Harn Yawnghwe on Rohingya crisis in an exclusive interview to RTD

There seems to be no end in sight for one of the world’s worst humanitarian disasters, which erupted on the border between Myanmar and Bangladesh almost a year ago. Nearly a million Rohingya refugees still remain in overcrowded camps in Bangladesh after fleeing violence and persecution in Myanmar. To find out more about the past, present, and future of the Rohingya crisis, RTD contacted Harn Yawnghwe, head of the Brussels-based Euro-Burma Office (EBO), which promotes democracy in his home country. The peace activist, who is also the youngest son of the country’s first president, Sao Shwe Thaik, shared his insight in an exclusive written interview.

The past

“Rohingya means people from Rohan or Rohin = Rakhine. People say we have never heard of the name Rohingya before, so they did not exist,” Harn Yawnghwe wrote. “At independence the 1947 Constitution said all people within the borders of Burma are citizens. The Rohingyas were there at that time. They had ID cards identifying them as Rohingya and citizens. The government’s Burmese Broadcasting Service had a Rohingya-language program. So the Rohingyas existed and their identity was officially recognized.”

However, it all began to change after General Ne Win seized power in a military coup in 1962. The military ruler “launched a program of Burmanization. He wanted a homogeneous society like Hitler wanted for Germany” in a country with a predominantly ethnic Burmese population. After driving out foreigners from India, China, and Western countries, Ne Win “started to harmonize the people of Myanmar.”

RELATED: 'Some kind of genocide': Why a million Rohingya Muslims fled from Myanmar to Bangladesh

“It became illegal to learn to read and write one’s own ethnic mother tongue. All education was in Burmese,” Harn Yawnghwe continued. The government crackdown spread to Christians and other ethnic minorities that professed Buddhism. “But the Muslims and especially the Rohingyas were a problem. They had distinct ethnic and cultural backgrounds and religious beliefs that would be difficult to eradicate and the Rohingya were concentrated together.”

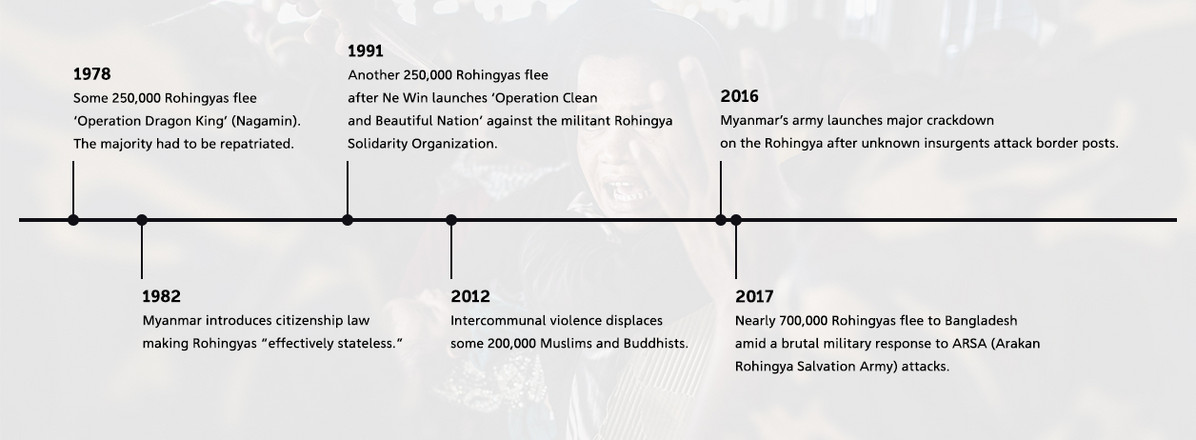

The authorities began targeting the Rohingya in a 1978 initiative dubbed ‘Operation Dragon King,’ which aimed to register citizens in Rakhine State (formerly known as Arakan) and expel the “so-called foreigners,” Harn Yawnghwe says. “250,000 fled to Bangladesh accusing the Army of forcing them out through intimidation, rape and murder.” However, Myanmar had to let 180,000 Rohingyas return.

In 1982, General Ne Win changed Myanmar’s citizenship law to require Rohingyas to prove that their ancestors had lived in the country for at least three generations. “If that law is uniformly applied to all people in Myanmar, the majority would become stateless,” Harn Yawnghwe said.

Nine years later, the military renewed its onslaught in ‘Operation Clean and Beautiful Nation,’ with victims attesting to the army’s violence. Though 250,000 Rohingyas fled, “the majority were also repatriated.”

“Since both attempts to kick out the Rohingya failed, I believe the Myanmar military decided to try one more time to reach their goal of a homogeneous society,” Harn Yawnghwe said.

The present

“To test the waters, inter-communal violence was instigated in 2012 resulting in 200,000 people – Muslim and Buddhists – being internally displaced,” Harn Yawnghwe said, referring to widespread clashes between Rakhine Buddhists and Rohingya Muslims that were sparked by the rape and murder of a Buddhist woman.

Later episodes of military violence in October 2016 and August 2017 forced nearly 700,000 Rohingyas to flee, while the ‘international community’ remained largely silent. “The Myanmar military may have calculated that international reaction would be even more muted since the western icon of democracy Aung San Suu Kyi was in charge of the country,” Harn Yawnghwe noted.

Aung San Suu Kyi, a Nobel Peace Prize laurate and Myanmar’s de facto leader, has been condemned for the persecution of the Rohingya, with some calling for her to be stripped of her award. Myanmar has repeatedly denied allegations of ethnic cleansing, insisting the latest military crackdown was a legitimate counter-insurgency operation. The government also says it is ready to take the refugees back.

“They are doing so to reduce international pressure. They are scared that the issue will be taken up by the International Criminal Court. They are not serious about repatriation because they say they will process 100 people a day. This means over 20 years to repatriate the Rohingyas. It will not happen,” Harn Yawnghwe stressed.

The future

“The Buddhist Rakhine and the Buddhist nationalists have stated very clearly that they do not believe that the Rohingyas belong to Myanmar. They say they do not want them back. The homes of the Rohingyas have been burnt and bulldozed by the Myanmar government, so it is not clear where they will live if they go back,” Harn Yawnghwe said.

“At one point, the government said they would live in temporary camps but how temporary is temporary?” he asked, noting that those displaced in 2012 are still living in temporary camps. He cautioned that it could be “very dangerous” for the Rohingyas to return. “Who will guarantee their safety and guarantee that it will not happen again. The only solution is to invoke the UN Responsibility to Protect Commitment and provide the Rohingya with a Protected Homeland in northern Rakhine in Myanmar,” he added.

“The Rohingya people have been oppressed since the 1970s” and, given the amount of persecution they have endured, it may seem “surprising” that militant groups like RSO or ARSA haven’t found much support among the population, according to Harn Yawnghwe. However, he noted that “most Rohingyas do not believe in violence.”