How ‘the father of PR’ Edward Bernays engineered consumerism in America

Freud’s theory of man’s consciousness seemed undeniable up until 20th century Europe. Freud analysed dreams and free associations of his patients and claimed his method allowed them to unveil the core of their ordeals and heal their inner wounds. Freud’s practice, called psychoanalysis, was based on the notion that people are driven not only by rational but also by irrational forces. He believed humans inherited sexual and aggressive patterns of instinctive behaviour from ancient times. Uncontrollably produced by the subconscious, such forces may lead to tragic consequences if not treated properly. Mass psychology became a major subject of Freud’s studies, after WWI. Dr Freud found it predictable that millions of soldiers were involved for no personal reason. The mass subconscious was a Pandora’s Box, which Freud thought was too dangerous to open.

Analysing Propaganda

The modern Latin word ‘propaganda’ was thought to have been coined in 1622, when the Catholic Church established the Congregatio de Propaganda Fide (Congregation for Propagating the Faith). Its purpose was to ‘propagate’ the Catholic faith in non-Catholic countries.

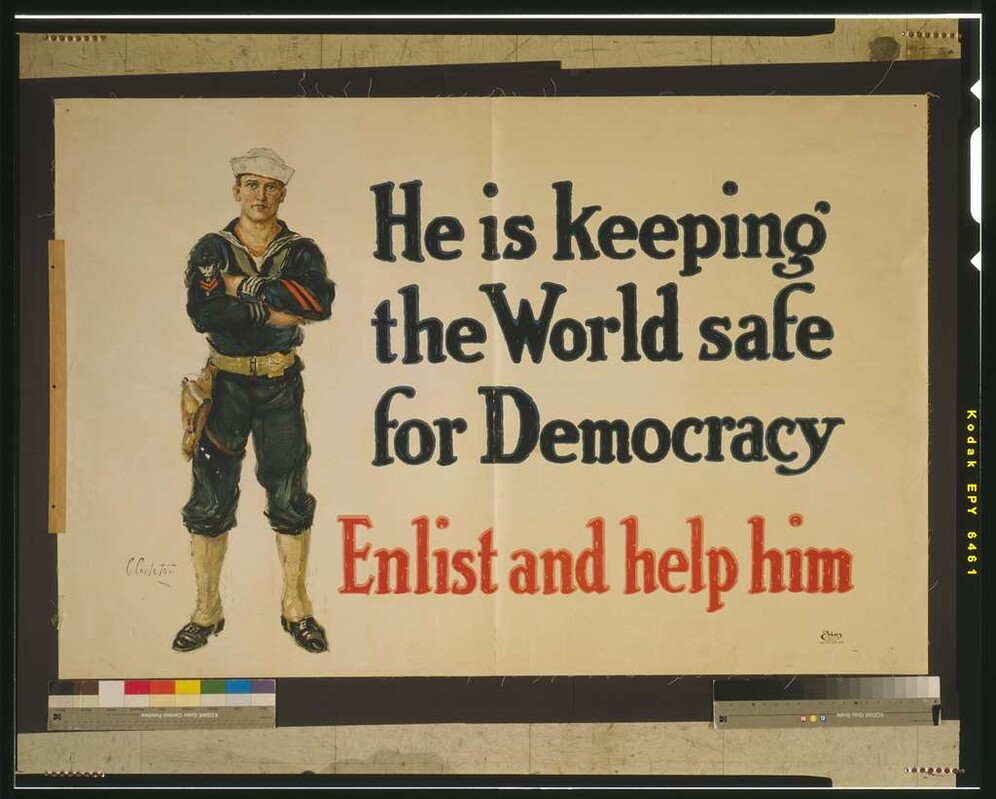

In 1914, with the start of WWI, this word became synonymous with large-scale military technology. Widely adopted, propaganda was effective in both encouraging national forces and weakening adversaries.

On another side of the pond, Freud’s nephew Edward Bernays received worrying correspondence from his uncle in war-torn Austria. Propaganda’s success wasn’t a secret to Bernays, a press agent in the newly formed American Public Information Committee. There Bernays received his first lessons on how to control the public’s subconscious.

He was tasked to voice American WWI interests to the public. US President Woodrow Wilson said American soldiers would fight not to restore the Empires but to bring democracy to the Old World. Bernays successfully promoted this idea and justified military action as an absolute necessity, bringing more than 4,500,000 Americans to the Army.

At the end of the war, the US was mourning the losses. Almost 17,000 American soldiers died, with more than 200,000 injured. Shocking numbers could overshadow political success. But Bernays knew how to distract the unwanted attention. Instead of listing the dead, he coordinated the media to focus press on heroic and touching stories. Widely portrayed a s a ‘liberator’, Wilson remained the mob’s hero.

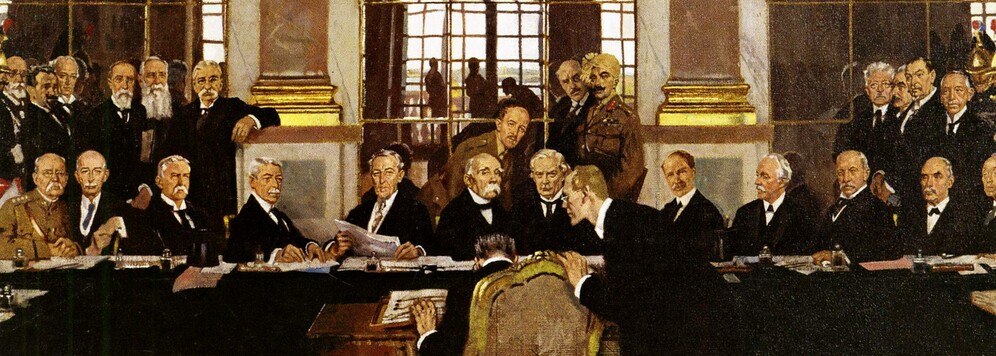

Bernays’ astonishing success didn’t go unnoticed, and soon the President invited him to come along to attend the Peace Conference in Paris. The war-time experience made it clear for Bernays how to manipulate the masses by feeding propaganda to the crowds. But what if a similar practice was used in ‘peaceful’ commercial interests?

… in other words, Public Relations

As a public relations counsel, Bernays soon became in demand. Waiting for the miracle, American business leaders visited his office, just like Freud’s patients did. But the therapy they wanted was much more expensive. One client was the President of the American Tobacco Company. He asked Bernays to turn American women into active smokers.

In the early 20th, a woman in the US could face jail time for wearing a short skirt. No doubt, smoking women would be seen as something utterly obscene and unacceptable. As nothing was known about the health risks of smoking at that time, the tabu was purely sexist in its roots. It was hard to believe that such an imperative could be crashed or disregarded.

To solve the dilemma, Bernays asked his uncle’s former student, Abraham Brill, who was then considered a leading New York psychoanalyst, for help. Bernays wanted to know what meaning American women saw in smoking.

But how was it possible to link these notions and demands of tobacco companies, and fulfil women’s needs on top of that? Democracy became the perfect bridge! Bernays decided to tie women’s smoking to their liberation from male oppression. He also drew a direct line between a cigarette and a symbol familiar to every American — a torch from the Statue of Liberty’s hands.

In a sense, the cigarette was a “torch of freedom” for women, a symbolic penis they never had. Bernays trained a group of models to a parade in New York during national holidays. On cue, they took out cigarettes and lit them in front of dozens of cameras. The giant banner behind the ladies said: “The Torch of Freedom.”

Bernays did not have to pay the press. The next morning this story was on the front page of every newspaper in America, a terrible scandal and noise arose, prompting public discussion on women’s liberation from men’s oppression.

Even today, smoking actresses are still recognised as independent and strong when smoking is almost taboo once again. For decades the desirable look became widely associated with cigarettes despite being completely irrational. But what happened after, fascinated by Bernays’ success American corporations began demanding something else. They didn’t want to alter their products to fit the customer, they wanted customers to play by their rules instead.

From need to desire

Having flourished during the war, American industry faced a new challenge in the late 20s. Consumers stopped buying new products prompting overproduction. The goods were too high quality to be replaced quickly. Back then, dominating consumption culture dictated a need for durable and practical goods. No matter, cars or shoes, all the products were seen as necessities.

In 1933, Franklin Roosevelt became President of the US and held this position for three terms — unprecedented for the United States. Roosevelt declared war on big business's influence on the White House and set out to centralise the economy.

Roosevelt’s struggle to centralise the economy was publicly endorsed by Goebbels, who at the same time was inspired by Bernays’ works.

Roosevelt’s approach was defied by corporations who had different views on democracy. Instead of active citizenry, they called for active consumerism and wanted Bernays to form a new society.

Bernays began experimenting with techniques of mass-consumer persuasion, which are well-known nowadays. He promoted a new line of women’s magazines owned by William Randolph Hearst, the Cosmopolitan founder. Bernays glamorised the magazine by filling it with scores of adverts, often featuring his clients’ products.

The commercials with film stars occupied the women’s press. Product placement in the film industry was pioneered by Bernays as well. He also dressed film stars for premieres, often in clothes and jewellery produced by his clients. With the help of Bernays, car producers began linking vehicles with status in their promotion.

American consumers began adapting to the new reality. Forces of manipulation, backed up by commercials and persuasion techniques, were gathered in the new PR advisers' hands, inspired by Bernays’ books, where he detailed his practical experience. They studied people’s inner desires and then “satisfied” them with consumer products. Bernays was working on a new way of managing the irrational mass. He called it the Engineering of Consent. Bernays agreed democracy was possible when people make conscious decisions. However, he still thought public opinion must be carefully orchestrated. He saw public relations as a crucial bridge which linked big businesses, government and the masses.

In 1939, the New York World Fair's theme was the unification of democracy and American business, and Edward Bernays was listed as the principal consultant. The show featured a giant white dome called Democracity built by General Motors. The model of democracy, in which government and business go hand in hand, ultimately won out.