How the World Defeated Polio

At the end of the 19th century, people around the world faced massive polio outbreaks that claimed thousands of lives. Poliovirus has swept across Europe and the United States, killing mostly children. There is still no cure for the disease. It was only conquered after a vaccine was invented and for decades the virus was considered almost eradicated from America, Europe, Asia and Africa.

However, the vaccine now appears to be useless against new virus mutations — the emergence of which could be caused by the vaccine itself. Is it possible to break this vicious circle?

Poliovirus in history

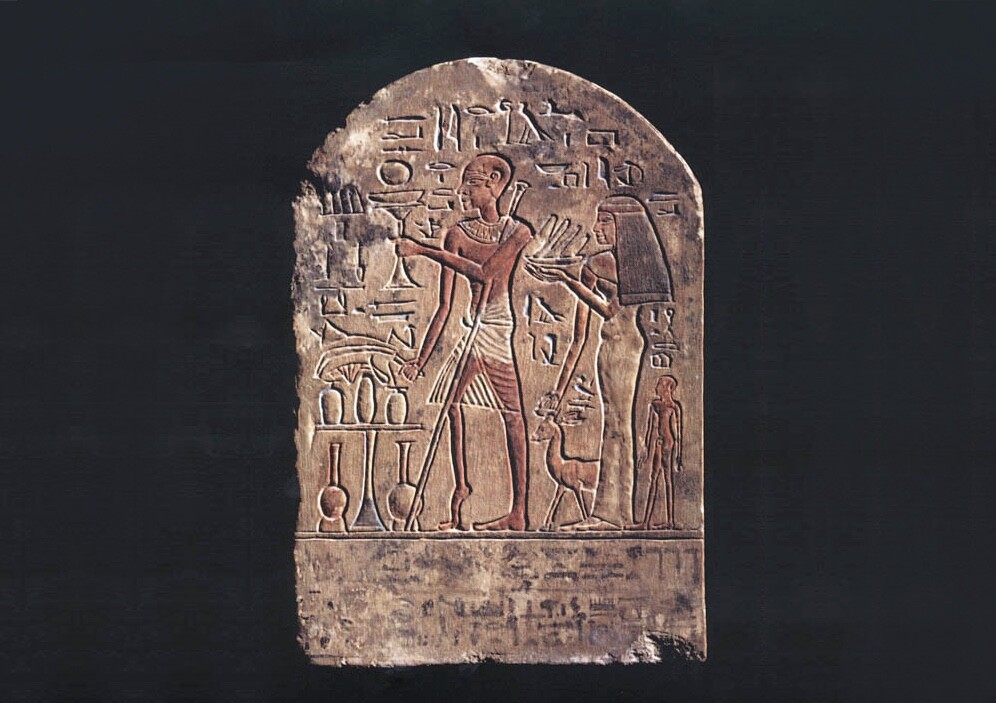

The history of Poliomyelitis dates back to ancient times. For a long time, doctors hadn’t recognised the illness which had rarely culminated in an outbreak.

The earliest portrayal of the course of polio is an Egyptian bas-relief from around 1500 BC. It shows a minister with his right leg distorted by infection.

Mostly a childhood disease, polio mainly affects children under five. Polio attacks the central nervous system and may cause paralysis, which often develops into a lifetime chronic illness.

The prominent Scottish novelist Sir Walter Scott was left lame after surviving polio when he was a child in 1773.

Outbreaks occurred in Norway during the 1860s, and by the 1940s the whole of Europe had been conquered by the disease.

Each summer in the 20th-century polio was an infection, terrorising American kids. President Franklin Roosevelt contracted polio in his early 40s and lost his ability to walk.

Roosevelt launched the non-benefit Georgia Warm Springs Foundation in 1926 to support polio victims. He built a recreational facility on the site of the Springs where he would come to receive treatment. He later founded the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, a charity, which united health scientists and volunteers who could assist the victims of polio complications.

The situation got even worse at the time of the Great Depression. In 1938 Roosevelt decided to appeal to the public for help. At a fundraiser meeting, celebrity singer Eddie Cantor jokingly called on people to send dimes to the president, coining the term the ‘March of Dimes’. The public took his appeal seriously, flooding the White House with 2,680,000 dimes and thousands of dollars in donations. More than two hundred million dollars was sent to support the fight against Poliomyelitis. Also, the National Foundation for the Fight against Childhood Paralysis actively invested in scientific research on the prevention and treatment of the disease.

Anti-Polio Vaccine

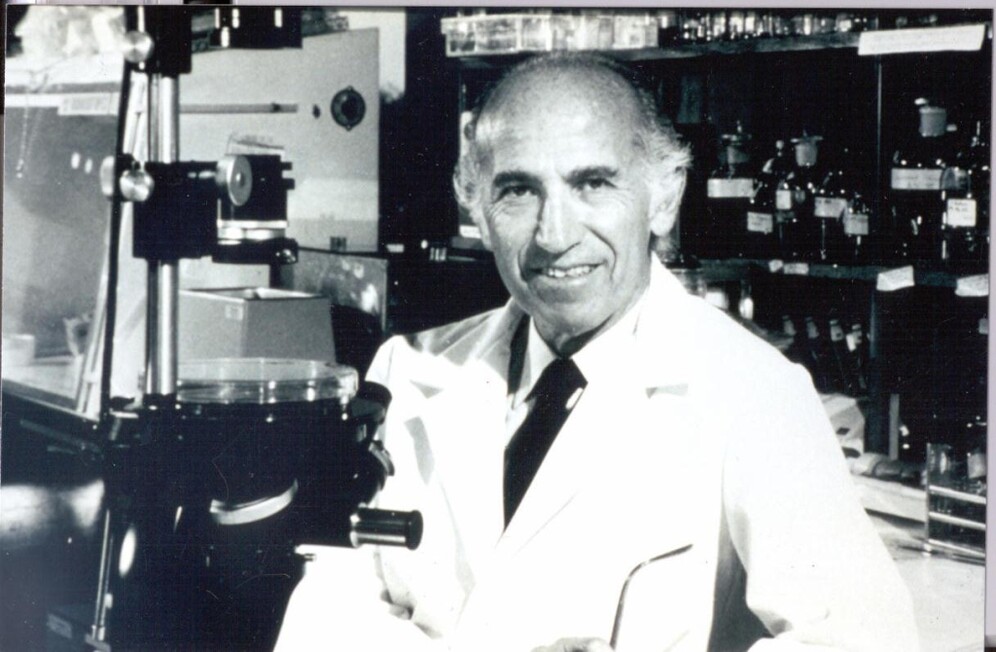

The first vaccine approved for mass production was unveiled in 1953 by Dr Jonas Salk. On March 26, speaking on a national radio show, he said his vaccine was successfully tested against poliovirus.

It came just a year after the US faced the worst polio outbreak in history. Over 3,000 people died, 21,000 were left paralysed, with over 50,000 infected, most of them children.

Salk’s vaccine consisted of the inactivated polio antibody and was administered through injection. Salk succeeded in growing colonies of polioviruses in monkey kidneys. Though in 1955, when the vaccine was officially licenced, Salk woke up a national hero, the testing methods he used would be considered unconventional today. Dr Salk tested the vaccine on himself, and his wife and children.

At the same time, another type of vaccine was introduced even though it drew much less attention. Albert Sabin created the so-called live attenuated vaccine. It was designed to be given orally, often in a sugar cube. It was much cheaper and easier to administer than Salk’s version. The vaccine contained live viruses, a fact which concerned many because of its potential risk of igniting the disease. During the rest of his life, Sabin had been trying to convince the public his live-virus cannot cause paralytic polio. Salk, in turn, said his vaccine was totally safe. However, Sabin’s solution was considered risky enough to be recommended by the Federal Advisory Panel who gave their votes to Salk.

Five companies received permission to manufacture the Salk vaccine. Unfortunately, a disruption in the production process at one of them, Cutter Laboratories, meant a drug containing a live and unweakened poliovirus was released. A dangerous vaccine was injected into 120,000 children. About 40,000 had mild Poliomyelitis, 56 children were paralysed, and five died. The “vaccinated” children infected those around them. As a result, five more people died, and 113 were paralysed.

Sabin’s vaccine, however, remained in the shadow of the Salk’s success. That changed in 1957 when a delegation of Soviet scientists visited the US. At that time, polio outbreaks were national issues in many countries, including the Soviet Union. In the mid-50s from 10-13,000 new polio cases were registered in the Soviet Union. The trend was so frightening Soviet scientists were allowed to visit the United States to learn about the vaccine. Mikhail Chumakov, Marina Voroshilova, and Anatoliy Smorodintsev arrived to see the Salk’s vaccine, but that was a chance for Sabin too. He realised that starting wide-scale production of his vaccine would be impossible in the US. Sabin convinced the Russian scientists his vaccine with living viruses is no less effective and much cheaper than Salk’s version.

For several months Soviet scientists worked both with Salk and Sabin and returned to the USSR with two working polio vaccines. Sabin handed over a sample of the live vaccine at the very last moment, just before takeoff. In 1959, 10 million Soviet children were vaccinated with Sabin’s oral vaccine.

Mikhail Chumakov investigated how best to deliver the vaccine into the intestines, so the virus doesn’t get lost in the mouth, where it does not multiply. As a result, he came up with the idea of making a vaccine in the form of candies. After a successful Soviet trial in the 60s, Sabin’s vaccine was approved for manufacture in the US. The World Health Organisation started to use the Sabin vaccine made in the USSR.

Is polio truly conquered?

“A failure to eradicate polio could result in as many as 200,000 new cases every year, within 10 years, all over the world”, claims the WHO. Although in 2018 the organisation announced polio cases globally had decreased by over 99%, today the rate is growing amid the fight against Coronavirus. In Sudan, dozens of minors have been hospitalised after contracting a new vaccine-derived type of a virus. Their median age is 31 months.

For two years African epidemiologists have been ringing alarm bells over the growing number of infections. Routine immunisation was stopped in many African countries due to the COVID pandemic and mutated poliovirus has quickly spread around Western Africa. Samples collected show the virus is derived from the vaccine and has successfully mutated so can quickly spread like the wild type. No wild poliovirus has been detected on the continent since September 2016.

The sets of small mutations in the genetic code of the virus show the measures taken by the WHO and local health organisations, in general, have seriously reduced the number of victims of mutant varieties of the vaccine poliovirus. However, they could not wholly suppress their spread.

Moreover, the data collected by scientists indicate that outbreaks of this form of polio are increasing. This comes as the overall proportion of people who have developed immunity from the old vaccine is rapidly decreasing.

Efforts to eradicate poliovirus has seen an increased risk of mutant forms of the weakened virus emerging that can affect immunocompromised children and adults after a previous outbreak has ended.