The Forgotten Epidemic: How the USSR Defeated Smallpox

In the 1959-60 winter, Moscow was on the verge of a smallpox epidemic. The deadly infection was brought to the USSR by poster artist Alexei Kokorekin who had returned from a business trip to India. However, thanks to doctors, healthcare workers, and secret services, a massive virus outbreak was prevented. RT Documentary sheds light on the declassified story about smallpox in the USSR. To learn more, tune in to the premiere of our new infobite on YouTube tomorrow!

Many consider the measures taken today to combat the coronavirus excessive and burdensome. However, they cannot compare to the rapid and robust reaction of the USSR to a potential epidemic of smallpox at the turn of 1959–60. Then, quite unexpectedly, Soviet healthcare demonstrated its effectiveness just when it was the most needed.

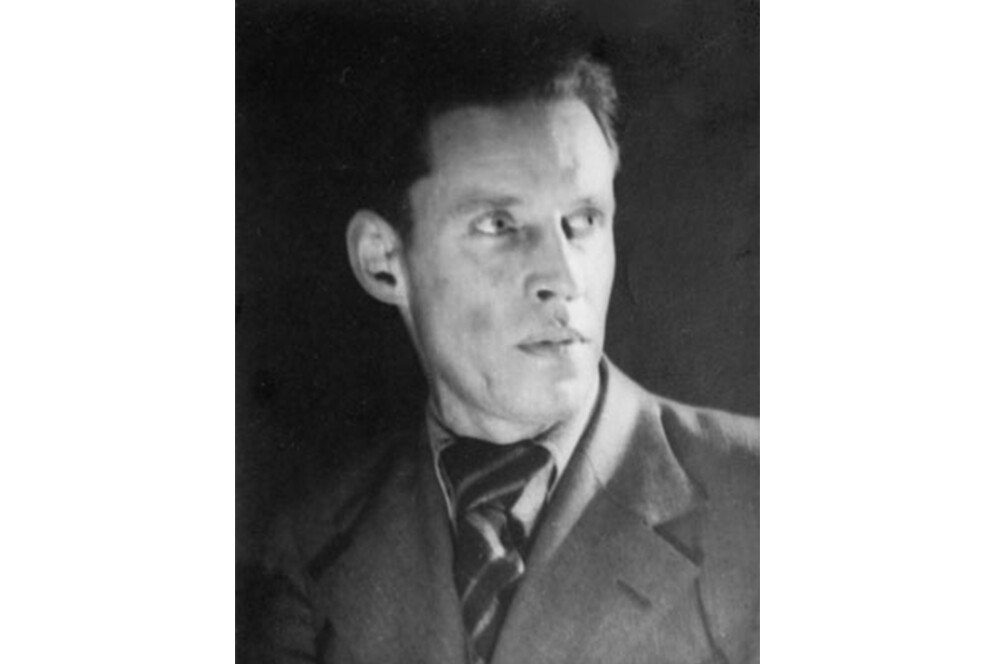

How we got into the smallpox story

“In the winter of 1959, we got into the story of smallpox. The artist Kokorekin returned to Moscow from a business trip to India. He returned a day earlier to spend a night with his mistress,” writes surgeon Yuri Shapiro in his book ‘Memories of a Life Lived’.

“The next day, having timed the arrival of the next flight from Delhi, he went home, where he surprised his wife with a bunch of presents from exotic India,” continues Shapiro.

When travelling to places where disease was endemic Soviet citizens were compulsorily vaccinated. However, Kokorekin somehow escaped vaccination against smallpox, although his medical record said he had been.

In the evening, Kokorekin felt ill. His family doctor diagnosed it as flu. But he deteriorated quickly and developed a high fever and a strong cough, with a rash spreading over his body, so his wife called an ambulance.

The deadly diagnosis

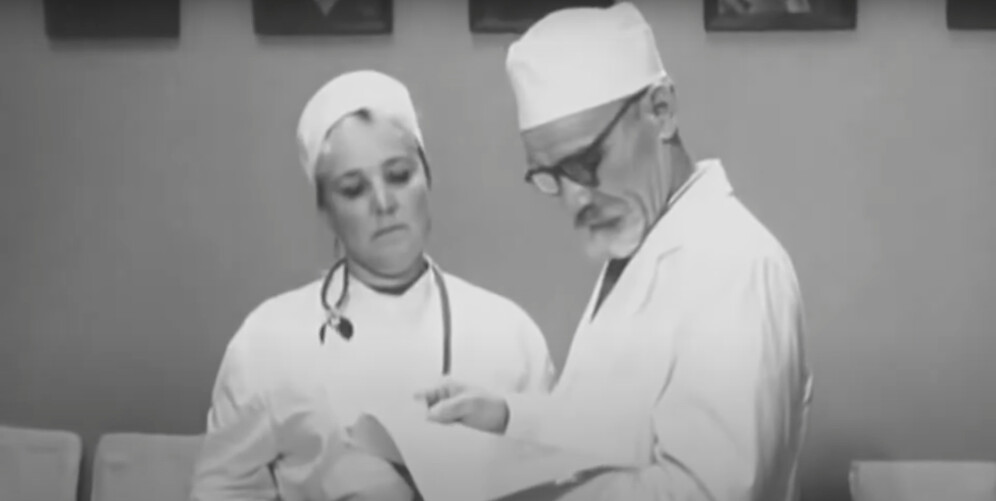

The artist was taken to the infectious diseases department of the Botkin Hospital in Moscow, where Yury Shapiro was then working. Soviet virologist Emma Gurvich, who was working at the Mechnikov Research Institute of Vaccines and Serums, writes that the greatest clinicians came up with various diagnoses: from plague and typhus to drug dermatitis.

At first, smallpox wasn’t even an option: the virus hadn’t been detected in the USSR since 1936. But, as a young graduate student came up with the diagnosis, “all the scientists sushed at her”.

Kokorekin died three days later, on the night of December 30, 1959. Two days after his death, two nursing staff members from the infections diseases department who had contact the artist also died.

A day after the artist’s death, the emergency room nurse who took care of Kokorekin and his doctor fell ill. Then it was the turn of a young man, lying in the ward on the floor below, whose bed was just under an air vent. Then it was the hospital stoker, who passed by Kokorekin’s ward to look at the celebrity.

Variola vera

Variola vera, or natural pox, has been one of the most terrible diseases for many centuries, destroying the population of entire villages, cities and even countries. In the 8th century, a third of Japan’s population died. In the 16th century, smallpox, brought by the European Conquistadors, wiped out more than half of the indigenous people of the New World. In Europe, by the beginning of the 19th century, up to one and a half million people died from smallpox annually.

In Soviet Russia, smallpox was defeated by employing massive vaccination. While in 1919, the number of smallpox cases in the country was estimated at 186,000, in 1936, the virus was eliminated.

Twenty-three years later, smallpox was back.

When virologists’ worst fears were realised, the outbreak of the virus was reported to the country’s top authorities.

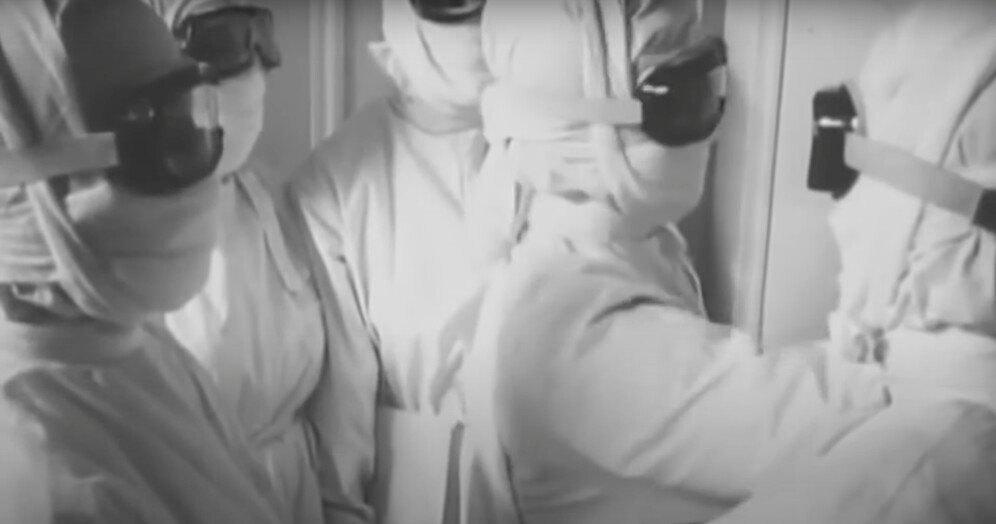

The reaction to the threat was instantaneous, total and highly effective. All forces that could be useful were mobilised. The Botkin Hospital was isolated. Troops were alerted.

Within hours, the internal affairs and the KGB forces worked out Kokorekin’s connections and tracked every step after returning to the USSR. They established the identities of the customs and border guards who met the flight, the taxi driver who drove him home, the family doctor and hospital workers. They moved from primary contacts to secondary contacts until the entire chain was tracked.

“Extraordinary precautions were taken in Moscow,” recalls Emma Gurvich. “Just like in a movie, we drove with a siren along the empty Garden Ring street from the institute’s laboratory to the Botkin Hospital. There were sick people and those who had contact with them. The driver and the epidemiologist accompanying us were wearing protective anti-plague suits.”

Three dead, millions vaccinated

Alexei Kokorekin’s family members and close friends were infected. In the article ‘The smallpox in Moscow, 1960: Facts and Figures’, Emma Gurvich and epidemiologist Galina Manenkova note that by January 18, 75 people who had been in contact with the deceased artist were identified. Nineteen of them got infected. Nine thousand three hundred forty-two people were placed under medical supervision.

Kokorekin’s friend artist Ruben Suryaninov recalls that in January 1960, people in protective suits came to his apartment and took him and his wife Nina to hospital, where they were kept for over a month. Before that, they were feeling sick but managed to fly to Riga and back. When this got out, Moscow and Riga airports, the flight crew, and plane passengers were quarantined.

Nikita Khrushchev personally controlled the KGB special operation in Moscow.

“There were no reports in the press or on the radio—as always, the government kept the people in the dark,” writes Golyakhovsky.

The doctor, and other health workers who had contact with Kokorekin, had to quarantine in the hospital.

Production of a vaccine against smallpox had to be organised in Moscow urgently. According to Shapiro, there was no smallpox vaccine in the capital, and at first, it was delivered from the Far East. In the article ‘40 years without smallpox’, scientists from Novosibirsk Sergey and Galina Shchelkunov said that it was in 1960 that a laboratory was organised at the Moscow Research Institute of Virus Preparations for large-scale production of an anti-smallpox vaccine that meets WHO requirements.

“In Moscow, a mass vaccination of seven million people was carried out in a week,” wrote The New York Times on February 3, 1960, confirming Gurvich.

“After this whole story ended, a banquet was organised at the Grand Hotel, where the medical staff and scientists could finally breathe a sigh of relief and have fun,” Shapiro writes in the conclusion of his story.

A young mistress is alleged to be why Alexei Kokorekin didn’t take the mandatory vaccination. He was allergic to vaccines and wanted “to be healthy and strong in love”.

Was he a true sentimentalist or, using modern vernacular, an anti-vaxxer? We’ll never know, but remember to tell this story to your anti-vaxxer friends.

Did you like the story? Then, don’t forget to tune in to the premiere of our new infobite on YouTube tomorrow!