‘Some kind of genocide’: Why a million Rohingya Muslims fled from Myanmar to Bangladesh

- Rohingya is a mainly Muslim minority in Myanmar’s Rakhine State.

- In 1982, Rohingya residents were denied full citizenship and gradually stripped of their rights.

- There were an estimated 1.1 million Rohingya people in Myanmar before August 2017.

- The UN has described the Rohingya as ‘the most persecuted minority in the world’.

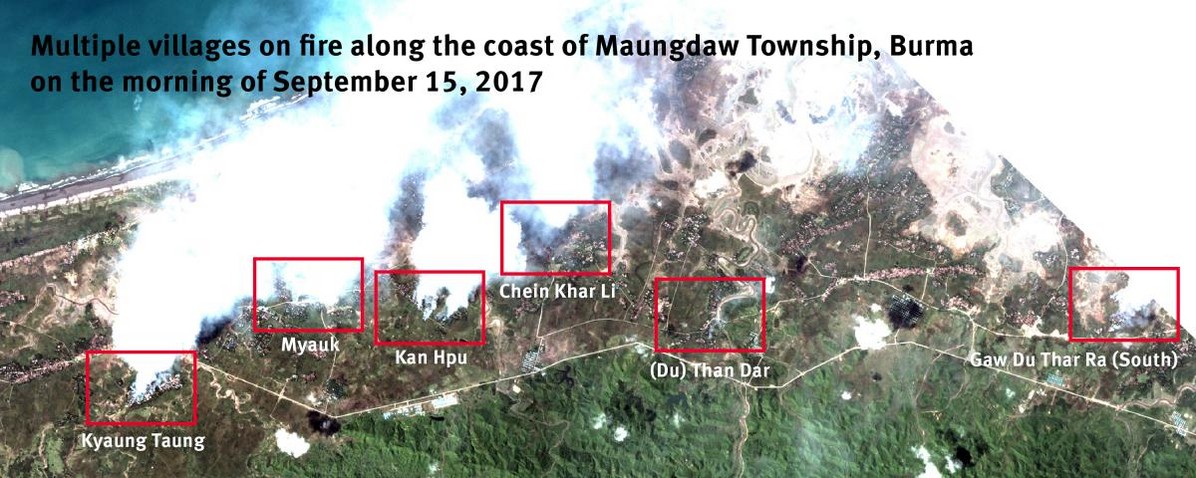

In August of 2017, streams of Rohingya people rushed to the Bangladeshi border fleeing a military offensive launched by Myanmar’s government. Beatings, lootings, rapes, slaughter and arsons – Rohingya refugees share distressing accounts of what they witnessed and suffered during the so-called “clearance operation.”

“On the first day, they killed my father. He was shot. We were at home and wanted to bury him. But they came after us,” a young Rohingya woman recalls.

As survivors fled, plumes of smoke rose in the background. “The military came in our village and started torching the houses. We ran toward Bangladesh, but they kept shooting and chasing us,” another refugee says.

Myanmar’s military, known as the Tatmadaw, says it descended on Rohingya villages after an insurgent group dubbed the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) killed 12 security officers on August 25 in a string of coordinated attacks on police posts.

However, according to a UN human rights office report based on interviews with dozens of Rohingya refugees, the atrocities began weeks before that incident.

It was “a good time to try to move the Rohingya out of Myanmar,” says Harn Yawnghwe, son of the nation’s first president, Sao Shwe Thaik, and head of the Euro-Burma Office, a Brussels-based organization promoting the development of democracy in Myanmar.

Myanmar, a predominantly Buddhist country, has long mistreated the Rohingya people, who it considers intruders that came from Bangladesh during British rule. In 1982, the Rohingya virtually became stateless, losing access to education, healthcare, employment, and the freedom to travel or marry. Even the term Rohingya is contested by the government, which instead labels them ‘Bengalis.’

-11-br.jpg)

“It’s surprising that [Rohingya] have not had an armed insurrection earlier,” Yawnghwe says. However, militant groups, such as the Rohingya Solidarity Organization from the 1980s and ARSA today, don’t get much support from the community. “Most people will not support an armed struggle, they want to live in peace,” Yawnghwe adds.

Myanmar and the UN have recently signed a deal setting out steps to return the displaced that would see the government building temporary housing. However, those willing to return fear they will linger in transition camps indefinitely and demand they be guaranteed safety and granted citizenship.

“We want to go to our home, without any camps” says Dil Mohammed, a Rohingya community leader living in a no-man’s land on the border between Myanmar and Bangladesh. “It’s some kind of genocide. After 2012, Buddhists moved many, many Rohingyas to Akyab in the middle of Rakhine State. [There,] Myanmar’s government set up an IDP (internally displaced people) camp with barbed wire. They still live in that IDP camp,” Dil said, referring to an earlier army crackdown on the Rohingya.

At the refugee camp in Bangladesh’s Cox’s Bazar District, there are few signs that the displaced are planning to go back to Myanmar. For many, the sprawling makeshift houses, wells, bamboo bridges, and footpaths are turning into a permanent home.

Learn more about the plight of Myanmar’s Rohingya people in RTD’s new documentary, Rohingya: Unpeopled.