Amok, Meryaсhenye and Grisi Siknis, the most mysterious mental illnesses from around the world

new version-21-br.jpg)

Culture-bound syndromes or 'exotic psychotic syndromes’ are sets of symptoms of psychic distress that seem to be confined to specific cultures. While each affected culture explains the phenomena within the strictures its own localised worldview, modern medicine struggles to understand or even classify them. Meanwhile, here's a selection of the most intriguing culturally-specific disorders:

Meryaсhenye

Meryaсhenye is the Russian version of what is known as 'Arctic hysteria', a trance-like state affecting both men and women within the Arctic Circle. Cases have occurred in the Kola Peninsula North of European Russia and along the Kolyma valley in Eastern Siberia.

The distinctive features of this syndrome include sufferers echoing what is said to them and responding to suggestion as if hypnotised. They also set off for the North Pole, claiming to be answering the irresistible summons of the North Star, and are impossible to hold back. Sufferers reach an altered state of consciousness, and after each seizure, they generally have no memory of what happened. During a fit, however, which can last for several days, they may wail, pour out torrents of speech, sometimes in unknown languages, or cackle.

Meryaсhenye is often collective. Groups ranging in size from a few people to entire villages can go into trances together. The Russian term is derived from the Yakut words “emiurekh”, a patient who repeats words and gestures, and “emerik”, one who, in a trance, complains at length about their fate in rhythmic chants. Most victims are indigenous, but some outsiders have been afflicted too. In 1870, the commander of a Cossack company stationed in the lower Kolyma told a doctor that 70 of his men were singing in unknown languages around nightfall.

During early Soviet times, Russian scientists from the Institute of the Brain tried to study the syndrome, but research was later shut down. The scarcity of observations means scientific explanations remained elusive. Reports of incidents have been on the rise since the end of Communist rule.

w watermark-18-br.jpg)

The indigenous people have not found a cure. They restrain sufferers to keep them from harm but tend to have a fatalistic view of the syndrome. Powerful shamans may use spells if they believe another shaman is behind the fit. However, they declare themselves powerless against the pull of the North Star.

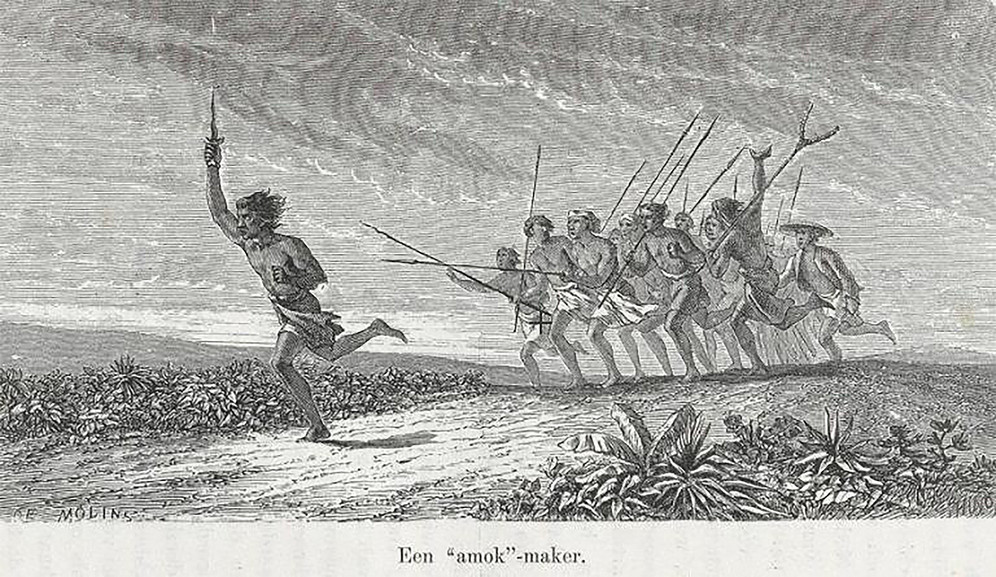

Amok

This explosive behavioural disorder has been observed in Indonesia for centuries and refers to a man going on a homicidal rampage.

Following a preliminary phase of brooding over wrongs, a generally trivial slight triggers changes in visual perception, as the perpetrator sees red or darkness and feels rage. Grabbing a weapon, he then attacks people randomly, often killing several. If the amok-runner is not “put down” or does not commit suicide during the episode, deep sleep or stupor follows, and then depression. Perpetrators claim no recollection of the episodes.

Indonesian culture has traditionally been tolerant of amok, in spite of its destructiveness. According to Malay mythology, an evil tiger spirit takes possession of the person, whose behaviour is involuntary and unconscious. European travellers of the 17th to 19th centuries were fascinated by Amok, notably Captain Cook. They believed it was a socially sanctioned custom.

Historically, Javanese warriors adopted the Indian warrior tactic of 'going berserk' in combat, attacking blindly to cause maximum damage, while shouting “amok”, before a glorious death in battle. When Islam came to Indonesia in the 14th century, amok became a type of kamikaze attack on infidels which pleased Allah, and unlike suicide, did not entail exclusion from paradise.

Amok was also used by the lower orders to rebel, releasing anger caused by gross injustice, and signalling that limits had been crossed. The threat of amok thus served as a check on the ruling classes. Similarly, when the Dutch took over, imposing a Western law-based government, amok murders of colonists in Aceh served as a form of protest.

In the 19th century, doctors believed the behaviour was opium-induced or had other physical causes such as gastrointestinal diseases or dementia. However, medical examination of surviving amok-runners by psychiatrists in the 20th century concluded that they were mentally ill, often suffering from schizophrenia.

Many specialists deny that amok is specific to Indonesia, however. They argue that the same behaviour has also been observed in the Philippines, among Laotian soldiers, and that mass shootings by alienated men in the United States is a contemporary version of Amok.

Grisi Siknis

Grisi siknis is is a form of frenzy experienced mostly by young girls, among the Miskito people who live on Mosquito Coast in Nicaragua and Honduras. The term derives, via a Creole dialect, from the English “crazy sickness”.

Victims report feeling fearful or irritable before an attack. They then lose consciousness and say they are being assaulted by a devil, who carries them off to have sex with them. Even though they may normally struggle to speak Spanish or English, the girls use those languages to talk to the evil spirit, if they believe he can understand. Sufferers start screaming, become aggressive, run away, and fight off the people trying to restrain them with extraordinary strength. When they wake up, they are often tied to a bed and report a bitter taste in their mouths, tiredness and no recollection of events.

Gisi siknis is considered a contagious epidemic. At the climax of an episode, victims shout out names, identifying people who are often the next to be afflicted. The disease often strikes multiple girls at the same time, in schools for example. Men are far less likely to suffer from Grisi Siknis, however, in recent years, symptoms have been observed in some groups of young men.

Doctors have found no physical cause for the seizures. Sufferers and relatives believe that the girls are victims of witchcraft. To resolve an outbreak, local communities turn simultaneously to pastors for prayer, healers for spells and to modern medicine to deal with any physical injuries.

According to some researchers, Miskito girls are expected to remain chaste and submit to men, but still attractive to appeal to potential husbands. In this context, grisi siknis may be a way to express sexual desire without being stigmatised. Some victims also complain they have previously been sexually abused.

The first case was recorded by an English traveller in 1850. Further occurrences were reported by the Moravian church during a revival in the 1880s. When Miskito Indians fled to Honduras to escape the Sandinista government and civil war in the 1980s, incidents occurred in the stressful conditions of refugee camps.

Psychiatrists are divided on the issue of culturally-specific disorders. On the one hand, cultural relativists believe mental health to be a culturally specific concept. Universalists, however, think their discipline simply fails to take into account the social context in which different diseases can be found around the world.

You can meet sufferers from the syndrome and those who try to cure it in RTD's film Grisi Siknis.