Show me your trash, and I will tell who you are: How garbage reflects our identity

In 1973, Professor William Rathje and students from Arizona State University developed and implemented the Garbage Project project to study household waste from homes in Tucson, Arizona. Surprising though it may sound, archaeologists have always studied garbage dumps as they’ve been around since ancient times. The archaeology of garbage or ‘garbology’ is the study of household waste and is the youngest speciality field. What can your leftovers say about you as a person?

“Our annual bottom-10 list, in which we salute the men and women who do what no salary can adequately reward,” open the rating of the most unpopular professions in science compiled by the Popular Science magazine for 2007. Then garbology, the science of waste, came fourth. This was when the world learned about garbology and the undeservedly forgotten William Rathje.

Studying garbage dumps isn’t an innovation in archaeology, as scientists have constantly researched peoples’ waste to find out how they lived centuries ago.

During WWI, the American Bureau of Food Distribution Supervision, analysing food waste, discovered Americans 25-30% of what they threw away was food even during a shortage. The administration even launched a “Clean Plate Club” campaign promoting frugality. However, the current scientific interest in garbage owes its popularity to Bob Dylan.

The art of garbage analysis

Alan Weberman, an eccentric left-wing activist and a writer, had been a passionate fan of Bob Dylan since the 1960s. Dylan was known to say he was utterly indifferent to coverage in the media.

Weberman didn’t believe his idol and visited Dylan’s house in New York in 1970 and gutted the singer’s garbage cans. A year later, the self-taught archaeologist wrote an article for Esquire magazine called The Art of Garbage Analysis.

In the article, Weberman revealed Dylan was reading the press about himself. Among the diapers (the singer and his wife, Sarah, already had three young children) and leftovers, Weberman found dozens of magazines and clippings about Dylan.

In Esquire, the author snidely went through the singer’s alleged disinterest in reviews. He was as vain as anybody and was no less worried about it. Weberman also studied the contents of the trash cans of boxer Muhammad Ali, playwright Neil Simon and other celebrities.

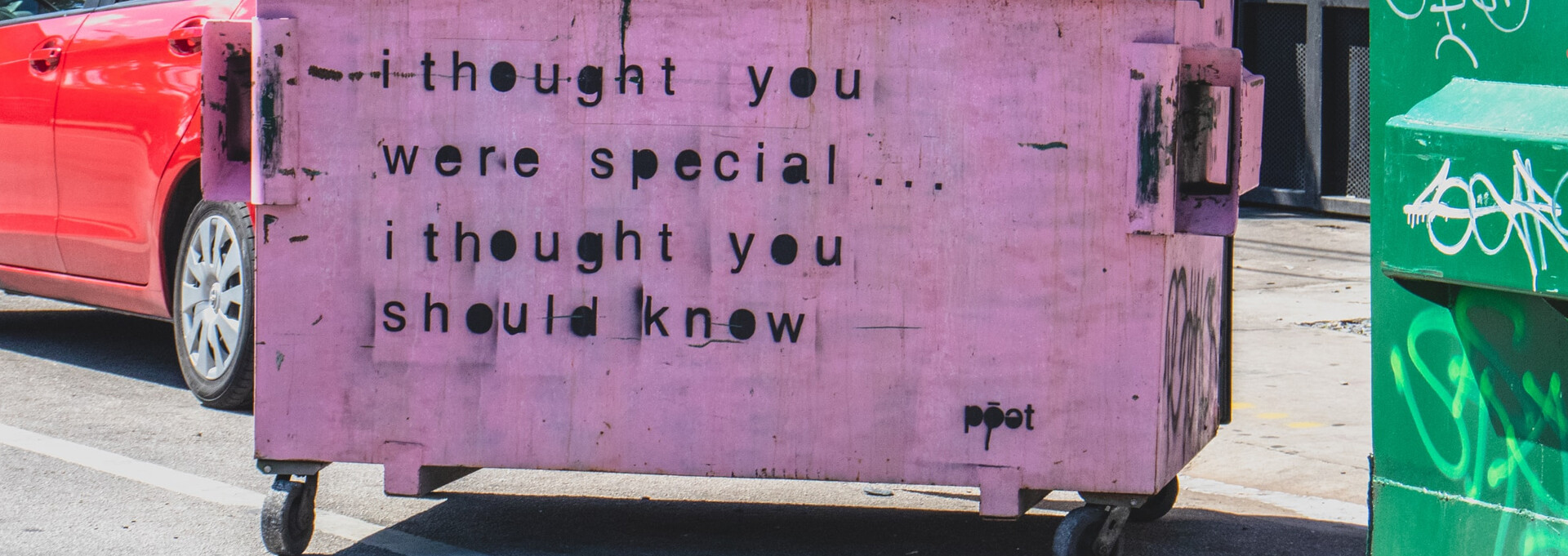

“Garbageology is a great way to find out what people are really like. I hope those who appreciate my pioneer work in the field will buy my upcoming book; You Are What You Throw Away. And remember: Garbage Is Powerful!”

Weberman’s experience interested the University of Arizona, as the Department of Archaeology was known for innovative research. It initiated the Garbage Project, headed by a specialist in classical Maya culture, William Rathje.

Surprising facts we reveal by studying the dumps

The first garbologist is considered to be William Lawrence Rathje, who introduced the term ‘garbology’ into science. In 1971, he became a Doctor of Anthropology at Harvard University. His research was initially associated with studying the pre-Columbian cultures of Mesoamerica, primarily the Olmec and Maya. But Rathje became famous worldwide, thanks to the Garbage Project.

The authorities in Tucson, the second-largest city in Arizona, assisted Rathje and his graduate students to study household garbage for many years. On the one hand, the scientists wanted to see what the residents had been throwing out. On the other hand, they were interested in comparing the data obtained from garbage study with those available to sociologists.

In 1973, Rathje and his students studied waste at a landfill in Tucson and found at least 10% of the rubbish thrown away was food. During a beef shortage, people started buying in bulk, and garbologists discovered they thew a lot of unused rotten meat away. The lack of beef paradoxically gave rise to its excess. But thrifty immigrants from Mexico threw away the meat least of all, using beef for stuffing in traditional pancakes and tortillas.

One of the research areas of the Garbage Project was dedicated to beer. Sociologists asked people how much they drank in a week, and archaeologists counted cans thrown in the trash.

Bins of 54% of participants had eight or more empty cans, and on average, 15 cans per week were drunk in these households. It also turned out poor people were less likely to admit to drinking beer. However, according to the waste analysis, wealthier people were more willing to tell the truth but significantly underestimated the amount of alcohol consumed.

When the Tucson project resumed in the 1980s, new “revelations” emerged. After the National Academy of Sciences published a study linking the dangers of animal fat to heart disease, the American Heart Association launched a public education campaign. The amount of fat thrown out doubled. But at the same time, the public didn’t listen to the doctors’ recommendations and did not turn to fish and poultry. Moreover, instead of steaks and chops, Americans began to buy hamburgers, bacon, and sausage (containing fat, but not in such an obvious form) from which the fat was easily separated. This allowed the drawing of far-reaching conclusions in the field of social anthropology.

In 1992, William Rathje published the book The Archaeology of Garbage. In the book, he shared many unexpected findings. For example, while American newspapers were actively writing about increased waste, up to 40% of all landfills in the United States were filled with old newspapers and magazines.

In short, the archaeology of garbage allows us to conclude that the food culture, people’s recreation habits and their way of life in general can be reflected in the contents of their trash cans.

“The whole of New York City rests on trash. And other cities around the world, too — after all, until very recently, garbage was not taken out for centuries. For a couple of hundred years, the streets of New York have risen by 2.7 metres. Ancient Troy, ancient Rome, Babylon, Jerusalem, Paris — all these cities are the same: you stand on the age-old accumulations of the physical remains of those who lived here before you. So, you’re always trampling on history,” said Robin Nagle, a professor at New York University and an anthropologist at the New York City Sanitation Authority, in an Esquire interview.

Nowadays, garbageologists also search for safe ways to recycle and utilise waste. Garbageologists implement various eco-projects, for example, the production of children’s Garbage 101 kits, which teach children the principles of responsible attitude to garbage.