The tragedy of the Soviet submarine which was silenced for almost a quarter of a century

Since the end of WWII, Russia hasn’t been involved in any serious conflicts at sea. However, there have been at least two dozen tragic incidents in peacetime.

The Cold War accidents were often hidden from the press. Most of these incidents were classified, and relatives received little or no information.

On October 21, 1981, in the Sea of Japan, the submarine under the command of Valery Marango was hit by a cargo ship. The crew fought for their lives as their burning sub began to sink. After three days, the sailors were rescued, but their story was ‘erased’, and the commander was jailed for ten years. The tragic event claimed the lives of 32 sailors and was swept under the rug. The XO of the boat Sergey Kubynin has been fighting for almost 40 years for justice and to restore the reputation of his crew and commander.

Soviet submarine S-178, where 27-year-old Sergei served as an XO, was returning from exercises in Ussuri Bay. Near the coast, the boat surfaced, and the commander and eleven officers went to the bridge. The sub was due to reach the Pacific Fleet base in Vladivostok’s Golden Horn in a few minutes.

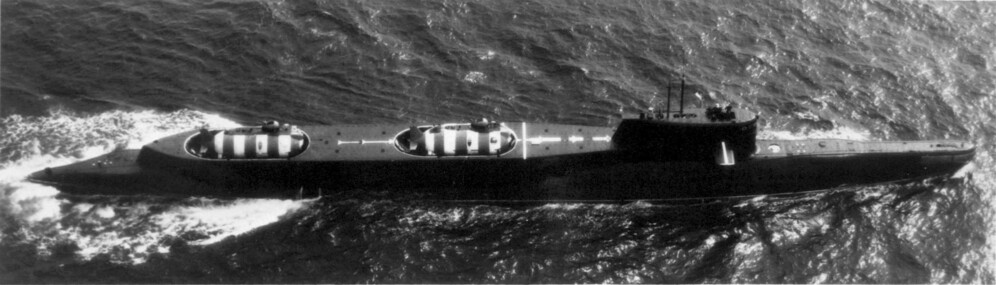

S-178

Known in the Soviet Union as a Project 613 type submarine, with the NATO codename Whiskey, the S-178 is a diesel-class, combat vessel built in the early Cold War period. Initially developed in the early 1940s, Germany’s U-boats heavily influenced the submarine’s design.

Along the shore, a refrigerator ship, REF-13 was heading towards the submarine with its lights off. That day, the REF-13 crew was celebrating the birthday of their XO, Victor Kurdyukov, and everyone on board was probably drunk. The cargo vessel received a good to go by mistake, so it weighed anchor with a drunken crew on board. Kurdyukov decided to surreptitiously make his way through the Soviet Pacific Fleet’s training area. The cargo’s lights were switched off to hide from the Coast Guard.

The submarine must have been visible to the REF-13’s sonar, but Kurdyukov stayed on course, apparently thinking it was a small ship that would clear out of the way.

The weather that evening was calm and clear, and the submarine crew was in a joyful and lively mood. They smoked, joked and were sharing plans for leave. As dinner on the sub was over, Kubynin was finishing checking the course to the base. A few minutes later the sonarman reported a vessel approaching the submarine at high speed. Stunned, those standing on the bridge deck turned around and saw the looming nose of the refrigerator ship.

The commander immediately ordered right full rudder, but it was too late. At top speed, the refrigerator ship hit the sub’s engine compartment and almost tore the boat in two. The commander Marango with the officers were tossed overboard from the bridge deck. Out of the twelve on deck, seven, including the commander, were saved by the cargo ship’s crew. With an eight square metre hole in its side, the boat sank in just 20 seconds in 32 metres of water. Sailors in the 5th and 6th compartments died in the first minutes after the hit.

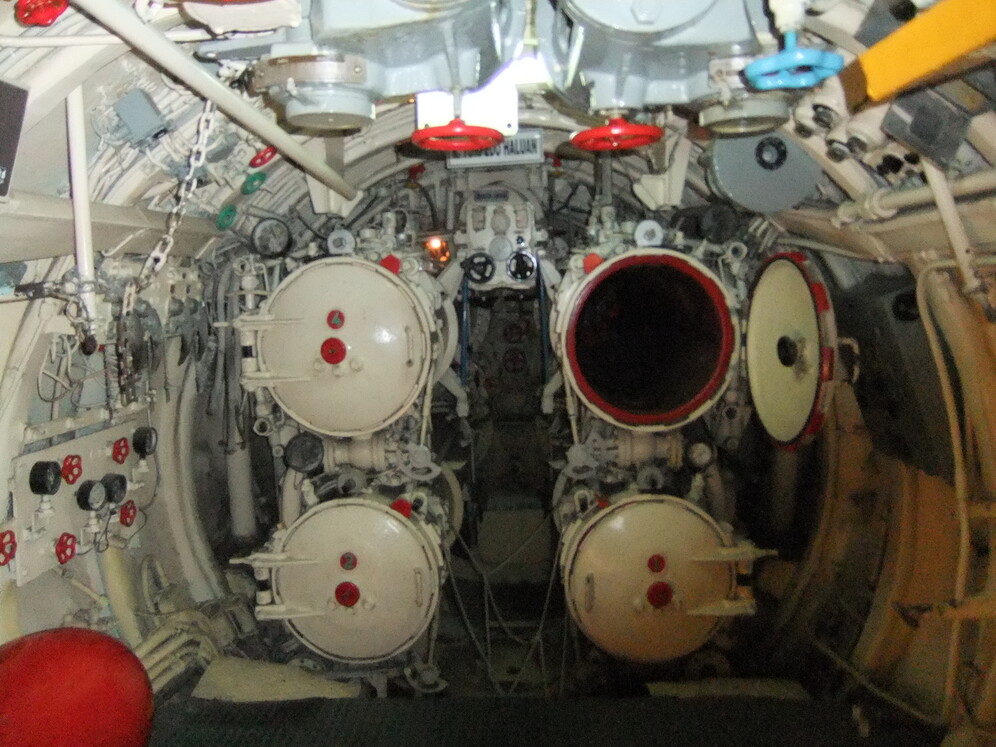

As parts of the submarine sand, the crew sent out radio beacons to send distress signals. Onshore, a rescue team responded to the accident. At the moment of impact, XO Kubynin was in the sub’s 2nd compartment, which was set on fire. Fearing they would run out of oxygen, the submariners tried to get to the bow compartment with other survivors, but the hatches were jammed. A sailor from the other side of the door was shouting he wouldn’t let anyone in. Opening the door could put the chance to flee the vessel through torpedo silos at risk. After two hours, the rescuers managed to communicate with the crew via the radio buoys. The sailors from the bow then let the survivors from the second compartment in.

Kubynin said when he entered the compartment, Vladimir Yakovlevich was lying on a bed, pale, white as a sheet, and only nodded in response to questions.

Four sailors were still stuck in the seventh compartment as the hatch through which they could get to others was jammed. Senior sailor Oleg Kirichenko and foreman Alexander Zykov were in communication for two hours until they said: “Goodbye. The water reaches our shoulders. “

All 34 survivors gathered in the nose compartment. XO Sergei Kubynin took command of the boat. The crew “handed over” the emergency buoy and began to report the situation to the rescuers via radiotelephone.

The rescue operation was led by Chief of Staff, First Deputy Commander of the Pacific Fleet Rudolf Golosov. He decided to save the submariners using the unique Lenok submarine. The rescue sub would be placed side by side with the S-178.

The damaged submarine’s crew would climb out of it through an empty torpedo tube. They would use emergency breathing equipment, and once they are out of the torpedo tube, they would be guided to the surface by rescuers from Lenok.

However, the involvement of Lenok sub was later found to be a fatal mistake. Its batteries had reached the end of their service life. Plus, its sonar didn’t function properly, and the search for the sunken sub lasted for more than a day.

The situation was compounded by a lack of experienced divers on Lenok.

In the meantime, the temperature in the compartments dropped to eight degrees. Kubynin had to boost morale and cheer up the sailors who were frozen to the bone.

There was also a box of badges on board, which read “First Class Specialist”, “Master of Military Affairs”, or “Excellent Worker of the Navy”. Kubynin awarded these titles to the submariners. Some of them he hailed for perfecting their skills and promoted others to a higher rank. The sailors became noticeably more cheerful.

On the third day, the rescue divers found S-178. They deposited breathing apparatus for the crew in one of the torpedo tubes and gave final instructions for the rescue. The divers gave the submariners a signal to exit by hitting the hull with a hammer.

XO Kubynin ordered the men to put on the apparatus and start flooding the compartment. The sailors began to crawl out through the narrow torpedo tube. The last to leave the boat was Sergey Kubynin. Losing consciousness from lack of oxygen, he ducked out of the tube and left the sunken sub.

But rescue divers were not waiting for him outside. They couldn’t believe anyone could flood the compartment and escape. Miraculously, they returned and found Sergey unconscious floating on the surface. He woke up in the hospital, where he spent several months with the bends, an embolism, oxygen poisoning, and pneumonia.

Relatives were summoned for identification under great secrecy and forced to sign a secrecy agreement. There was not a word in the Soviet press about the accident in the Golden Horn. The silence lasted for almost a quarter of a century. Several veteran organisations filed appeals to award Sergei Kubynin the Order of Lenin and the title of Hero of the USSR. But things didn’t go well: the departments chose not to stir up the past.

Sergei Kubynin filed an appeal with the Supreme Court to reopen Marango’s case and prove his innocence, but the military prosecutor advised him to keep quiet.

Despite the Soviet press’ silence, a monument to the S-178 submarine crew was erected in the Vladivostok Sea Cemetery at the mass grave on the first anniversary of the tragedy in 1982. The names of the 32 dead submariners are engraved on the granite tablets at the foot of the monument. Sixteen submariners were buried in the mass grave. Ten sailors were buried at their place of residence, the bodies of six were not found.

For almost 40 years the former crewmates have been trying to restore the good name of the commander. Kubynin even spoke with President Vladimir Putin during a visit to Vladivostok in 2016. The commander, Valery Marango, died in 2001 after being released from prison.

Recently a memorial deck for Marango was opened in Moscow in a private museum of a Russian prominent marine explorer Fyodor Konyukhov. But authorities still refuse to reconsider the sentence for the commander officially. Speaking to a Russian newspaper, a former Soviet Fleet officer said he sees no need in changing the verdict and blames Kubynin for failing to prevent the tragedy.