Who’s Naughty or Nice: China’s social credit system

Dubbed the “most ambitious project in social engineering since the Cultural Revolution”, China’s social credit system is being deployed on a countrywide scale starting this year. It aims to use a rating system to build a harmonious society with a reliable tool for regulating individuals and companies’ behaviour. Its stated goal is to help rebuild trust in China’s public and private institutions and steer the society towards a more sincere, moral and trustworthy future.

The idea to award every member of society a rating indicating their credibility and trustworthiness has been the plot of countless dystopian movies, so no wonder China’s social experiment has been met with apprehension and fear.

But there’s no use pretending technology hasn’t already redefined the rights of individuals around the globe, challenging their privacy and using the snippets of digital data they leave behind wherever they go against them. In this case, the conversation instead revolves around the human rights implications and whether the introduction of similar systems would eventually lead to building digital police states curtailing the rights of those who fail to conform.

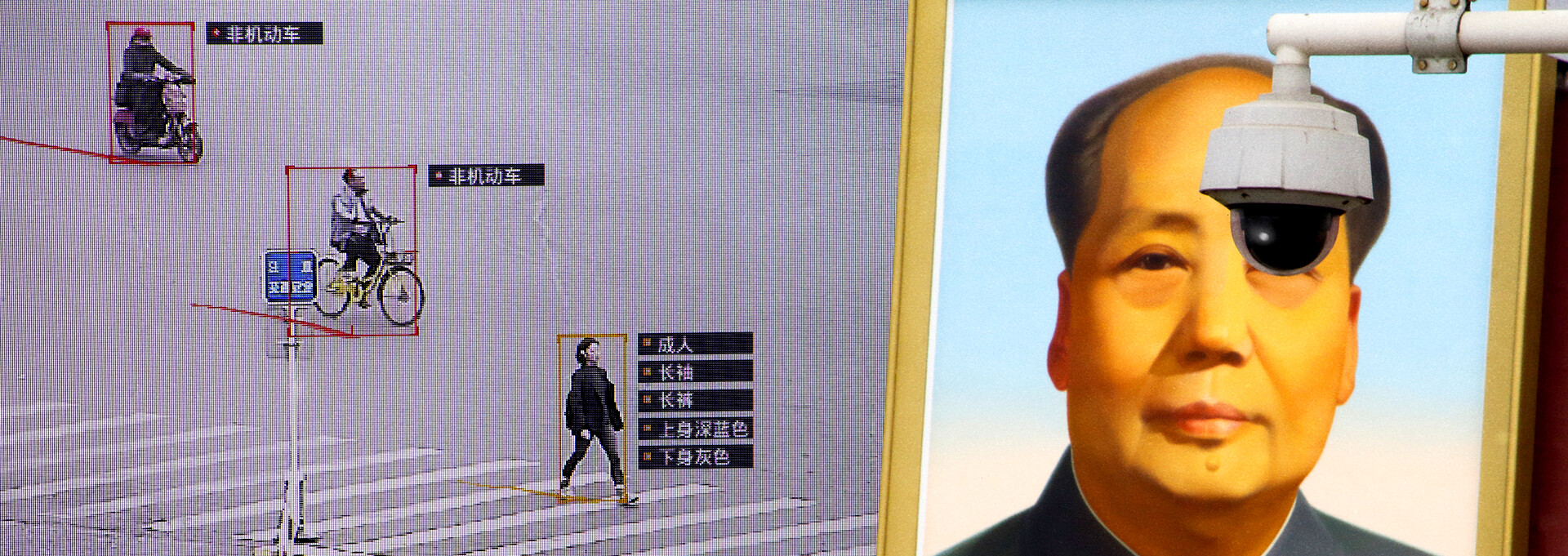

To begin with, the bold new initiative of the Chinese government isn’t that new. Envisioned over 20 years ago and formally launched in 2014, if only in a handful of cities, last year it rolled out nationwide, sending the media into a frenzy. Damned by the West as the most recent of the country’s innumerable human rights abuses, the newly introduced system of assigning each individual a rating based on his or her social merit is viewed as a means to punish unreliable citizens with the help of all-seeing surveillance systems, online monitoring, as well as tips from neighbours and coworkers.

The last adage is indeed a quote from the Planning Outline for the Construction of a Social Credit System — the project’s founding document issued in 2014.

Let’s take a look at how the system works. It’s pretty straightforward and has many similarities to the individual financial credit scores popular elsewhere. To begin with, every Chinese citizen gets a score of 1000 points. From there on it can either grow or drop depending on the person’s behaviour. One can gain points for all kinds of commendable actions, from taking care of ageing parents and engaging in charity work to paying taxes on time or even committing heroic acts. Whereas posting anti-government messages on social media, getting involved with religious cults, cheating on exams or jaywalking will cost one social point, and could even get one blacklisted. Sounds a bit like a computer game, where one’s goal is to collect rewards, avoid pitfalls and get to the next level.

Similarly, a series of bad decisions can get you thrown out of the game. In a Chinese context, that means being treated like a second-class citizen. Dropping to the lowest possible score of 600 can ban you from using public services, buying plane tickets, deny you a loan or even result in a public shaming campaign with your face and ID number displayed in public places. The internet is rife with accounts of people being denied hotel bookings or even access to prestigious universities based on their previous transgressions. On the contrary, high scorers get rewards, ranging from priority housing and employment, tax breaks, access to free gym facilities, and better consumer credit rates. Presently, the most you can get is 1300 points, and you’d have to work hard to get nearly that much.

The first experiments were a complete disaster, and surprisingly, was publicly acknowledged. A 2010 pilot in Suining, a county in Jiangsu province near Shanghai, didn’t last long, blasted by both the county residents and the media for using arbitrary criteria resulting in unfair scoring. The state-run Beijing Times newspaper went as far as comparing the system to the “good citizen” certificates issued by Japan during its wartime occupation of China. Although the Suining pilot was cancelled, it taught the government some valuable lessons.

Two years on it’s yielding results. According to the National Public Credit Information Centre, by the end of the programme’s first-year Chinese courts banned blacklisted potential travellers from buying plane tickets 17.5 million times and train tickets 5.5 million times. The report also said 128 people weren’t allowed to leave China because of unpaid taxes.

For anyone living in a culture where freedom of movement is considered sacred, and one’s ability to travel solely depends on one’s financial means, these statistics would sound like an account of life in a totalitarian state. But the Chinese don’t seem to mind. Once these staggering numbers were published on Chinese social media, they got many reposts and likes.

In China, people seem to be comfortable with the idea of being watched and, on the other hand, being able to check out their business partners’, neighbours’ and even potential love interests’ reliability and trustworthiness score. According to Merics analysts “wealthier, higher educated, urban respondents perceive social credit systems as an instrument to close institutional and regulatory gaps leading to more honest and law-abiding behaviour in society, and less as an instrument of surveillance”.

Suppose you grew up in a socialist state like the former USSR. In that case, you’d probably conjure up an image of public poster boards in town squares featuring wholesome faces of labour heroes or, on the contrary, “walls of shame” with photos of sorry-looking social deadbeats entitled “They bring dishonour to our city”…

Speaking of deadbeats: every Chinese can download a mobile app dubbed “The Deadbeat Map” displaying the location and identity of anyone within 500 metres who’s landed on a government creditworthiness blacklist. Why would anyone (unless they work for a tax office) want to know if they’re riding a bus next to someone who didn’t pay their taxes? But according to the Chinese, privacy is a small price to pay if what you gain in return is trust.

Over 75 percent of the mentioned survey participants said that “mutual mistrust between citizens” is a problem in Chinese society. Plus, China has a severe debt problem with the equivalent of $14 billion in bond defaults in 2018, according to Merril Lynch. So the government believes social pressure might incentivise some debtors to clean up their act.

Instead, it is a network of various data clusters run by banks, local government offices, credit institutions, travel agencies, shopping platforms etc. which, combined to produce a score characterising an individual based on his or her actions, behavioural patterns, previous legal violations etc. There are over 40 such social credit systems, which most people enrol voluntarily, unless it’s a criminal database, of course. Plus, if an individual believes there’s been a mistake in their social rating, they can object and get erraneous entries corrected. This right is spelt out in the clause on “The right to reputation and honour” of China’s Civil Code.

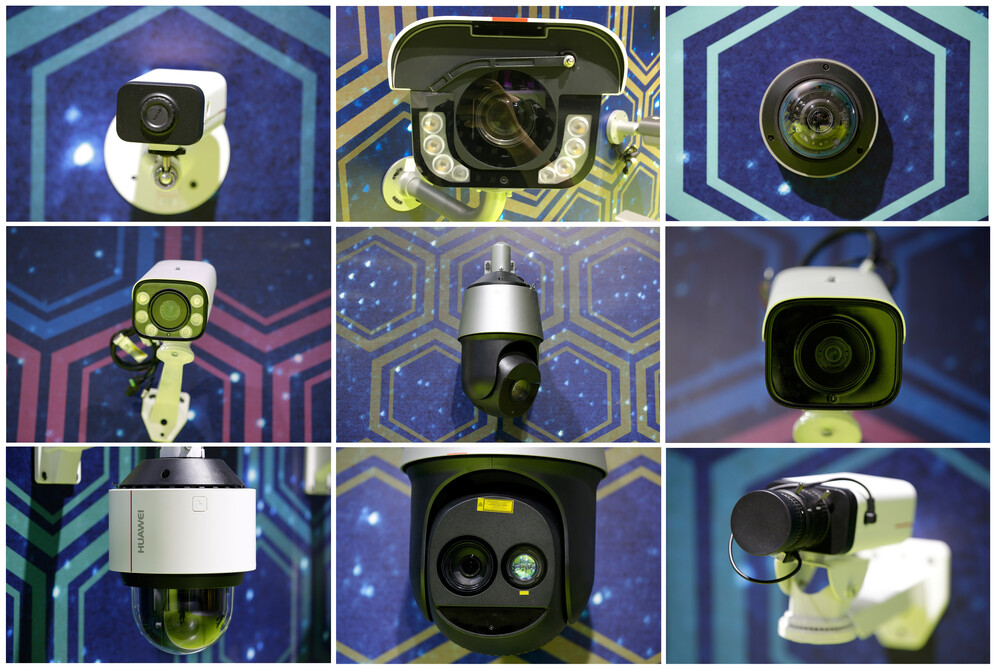

This isn’t to say fears about China’s social credit system are entirely unfounded. Some experts suggest China is much more open to abuse when it comes to access and use of personal data. It lacks a free media and the civil society that could draw attention to potential issues. Amazingly advanced face-recognition and data collection programmes mean the social credit system could indeed resemble a plot from the pages of “Super Sad True Love Story” — Gary Shteyngart’s novel set in the future where the Chinese yuan is a global currency, and people are obliged to wear an “apparat” with RateMe Plus technology.

The goal to eradicate vices ranging from poor driving to government corruption is, of course, a noble one. Still, the social credit system’s fair implementation would undoubtedly require some effective checks and balances to prevent it from materialising as a feared Orwellian scenario. But it’s also worth reminding ourselves that being on the forefront of the global push towards increasingly centralised and sophisticated surveillance, China is but a harbinger of the emerging trend. Rating systems similar to the social credit system will inevitably start popping up worldwide, assessing people’s social worth and putting them on the virtual but oh-so-consequential naughty and nice lists.