Santa Under Siege: Are Chinese Money and Russian Guns Threatening Peace in the Arctic?

"Arctic cold war: climate change has ignited a new polar power struggle,” warns The Conversation. “Move Over, Santa: Putin Claims the North Pole,” cries Canada’s CNBC. “How China’s Arctic empire will upset the global balance of power,” prophesies Newsweek. “World War 3 WARNING: UK to send HUNDREDS of troops to Arctic as Russia relations worsen,” screams The Express.

If you only read the headlines, you might believe tensions in the Arctic have reached a breaking point and that the world’s most fragile and pristine region is about to be wrecked by war and greed. The good news is that these doomsday scenarios are about as real (SPOILER ALERT) as Santa’s Polar residence. Here are four myths you won’t be disappointed to discover are entirely untrue.

Myth 1: Global warming spells the end of peace in the Arctic

The Arctic region is a haven of peace and good neighbourliness, but now the polar ice cap is melting, particularly in summer. This places the mineral wealth of the Arctic within human reach for the first time ever. So, can the current friendly set-up withstand the corrupting lure of riches?

Since 1996, the eight countries with land inside the Arctic Circle have collaborated through the Arctic Council. Canada, Finland, Greenland-Denmark, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the United States coordinate through this intergovernmental forum, where indigenous groups are represented as well. Areas such as search and rescue, the Polar Code, which sets navigation safety standards for this extreme environment, and environmental protection are all discussed here, but not issues related to military security. All decisions require consensus.

Despite competing claims over Arctic waters, the constant dialogue between countries that know what they’re talking about, because their citizens live there, has enabled these neighbours to solve problems and keep the area so peaceful that the Arctic Council was even nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize this year.

According to Igor Neverov, Russia’s Foreign Ministry official responsible for Nordic countries, “There are no military challenges there that will require a military solution.” US Ambassador David Balton, formerly a top State Department diplomat on Arctic issues, agrees. “The United States and Russia… have found ways to continue to cooperate in the Arctic,” he said. Norway’s foreign minister, Ine Eriksen Søreide, describes the Arctic as “a stable region because we work for it. It’s really hard work.”

-16-br.jpg)

To ensure that the region remains peaceful, the five states that border the Arctic Ocean signed the Ilulissat declaration in May of 2008, reaffirming their sovereign rights and their commitment to solving competing claims on the basis of international law and, in particular, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

But could the tales of fabulous untapped oil and gas reserves, particularly offshore, change the behaviour of Arctic nations? The United States Geological Survey estimates that 30% of the world’s undiscovered gas may yet be found beyond the Arctic Circle, particularly in Russia, as well as 13% of the oil. Since most of these natural resources are to be found onshore or within undisputed exclusive economic zones, none of the neighbours has an interest in undermining the legal framework that bolsters their sovereignty.

Non-arctic countries trying to avoid being excluded from the region can gain a foothold by applying for observer status on the Council. This requires that they make themselves useful by carrying out scientific work and agree to respect the Arctic countries’ current sovereignty. Thus, the UK markets itself as the Arctic’s nearest neighbour, calling the ocean “Britain’s back yard.” Switzerland was recently accepted as a permanent observer, claiming its Alpine peaks give it “vertical Arctic” expertise.

-17-br.jpg)

Asian countries don’t want to be left out either. China has dubbed itself a “near-Arctic country” to justify its presence in the area. It would like the central part of the ocean, which is still frozen as of yet, to be considered high seas where it could freely navigate and fish once global warming has moved fish stocks north. Indian scientists are studying the link between climate change in the Arctic and the monsoons. Singapore wants to be kept informed because it might lose out if ships shun the Malacca Strait and Suez Canal route in favour of the Northern passage.

While non-Arctic countries are keen to claim the Pole as common heritage for all, they tread softly to avoid being entirely shut out of the forum by the Arctic Council’s members. Not only would their undertakings in the region lack a legal basis, but they would be unlikely to go far without the logistical assistance of Arctic states.

Myth 2: Russia is trying to expropriate Santa

This is the spin Canadian media have put on Russia’s claim to 1.2 million square kilometres of water in the Arctic, in conformity with the UNCLOS. However, according to Michael W. Lodge, former Legal Counsel of the International Seabed Authority, “the true position bears little resemblance” to this kind of scenario because “the Arctic Ocean is no different to any other of the world’s oceans” and cannot legally be considered global commons if other rules apply.

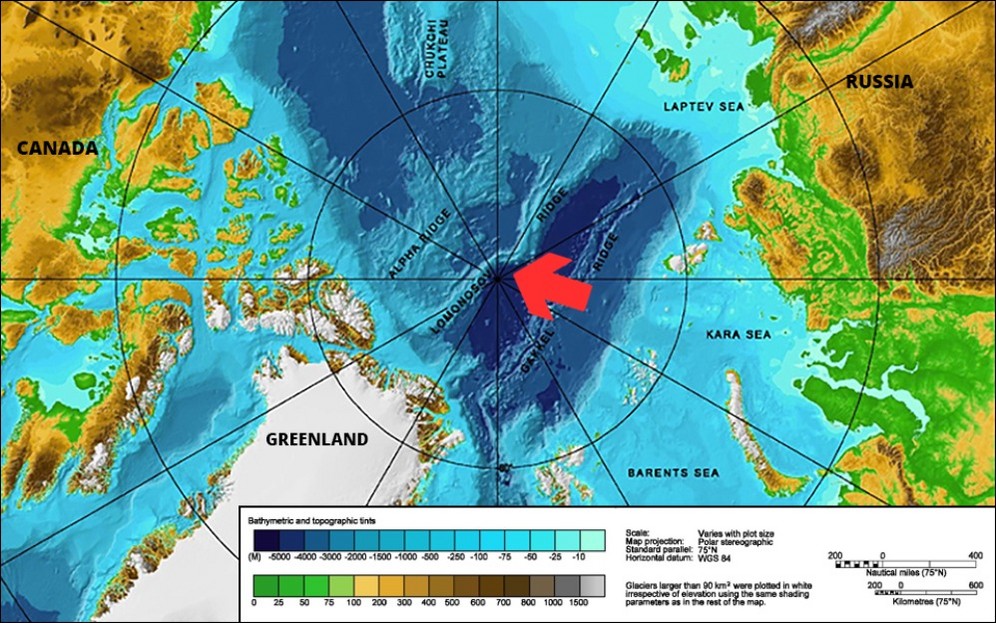

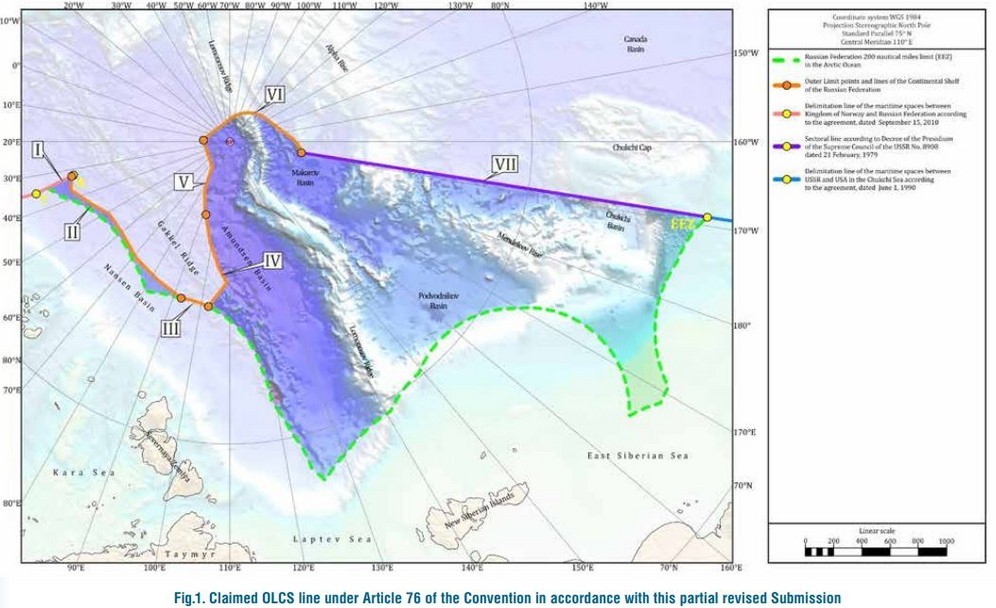

The 1982 Convention, which Russia signed in 1997, sets criteria for defining rights over the seas. It states that Arctic countries have rights to an Exclusive Economic Zone within 200 miles of their coast line. If Arctic countries can prove that the continental shelf extends further and can negotiate maritime borders with neighbouring claimants, they are entitled to mine the seabed and what lies beneath it.

In 2001, Russia submitted a claim to the Lomonosov Ridge within ten years of signing the convention, in accordance with UNCLOS rules. The ridge, which stretches from Siberia to North America via the Pole, is mostly less than 2,500 metres deep. Thus, if it belongs geologically to one of the continents, the relevant nation may mine 100 miles on either side of it.

The UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) asked Russia to produce geological evidence to support its claim. Russian scientists gathered data, most famously by sending a submarine to collect rocks in the sea bed beneath the North Pole in 2007. While there, they planted a titanium Russian flag on the seabed, 4,500 kilometres below sea level.

-18-br.jpg)

Canada’s then Foreign Affairs Minister Peter MacKay denounced the move on national television, saying, “We have established a long time ago that these are Canadian waters, and this is Canadian property. You cannot go around the world these days dropping a flag somewhere, so this is not the 14th or 15th century.”

Sergey Lavrov, Russia’s Foreign Minister, expressed surprise at this interpretation, saying, “Flags are usually planted when pioneers reach a point that has never been tread upon before. This was the case with the Moon, by the way.” As far as Russia was concerned, “the aim of this expedition [was] not to stake Russia's claim but to show that our shelf reaches to the North Pole,” he explained.

-34-br.jpg)

In any case, Santa has other suitors. In 2014, Denmark claimed the Lomonosov ridge as an extension of Greenland’s continental shelf and included the North Pole in its submission. Canada made a partial submission in 2013, which detailed its claims in the Atlantic Ocean and stated it would also furnish information about the Arctic at a later date. These are still pending, but at the time, Canadian Foreign Affairs Minister John Baird told journalists that "We have asked our officials and scientists to do additional and necessary work to ensure that a submission for the full extent of the continental shelf in the Arctic includes Canada's claim to the North Pole." Russia produced new scientific evidence backing its claim in 2015.

Canadian Arctic legal scholar Michael Byers believes his country is wasting its money pursuing the claim. “The scientists can say, ‘yes, there is a scientific argument, the Canadian continental shelf includes the North Pole,’ but only if you look at the science. The moment you look at the law it clearly becomes either Danish or Russian,” he said. As far as he’s concerned, this was merely a political move by then-Prime Minister Stephen Harper. “He didn’t want to be the prime minister who surrendered Canada’s claim to the North Pole,” Byers added.

What’s the point of going to so much effort then? Canada, Denmark and Russia have to make bids for their side of the Lomonosov ridge in case it becomes accessible and, thereby, able to provide welcome revenue streams for their respective public purses. However, the Pole itself is not about to become a drilling site.

“The North Pole is not what most people imagine. It is not a place with a candy-striped pole signifying the location of Santa’s workshop,” Byers argues. “It is, in fact, located in the middle of a large and hostile ocean. There are 4,000 metres of water at the North Pole. It is covered most of the year with shifting, moving sea ice. Temperatures often drop to minus 50 degrees. It’s one of the most inhospitable places on the planet and therefore has no economic value,” he said. However, while Global warming won’t turn the Arctic into the Riviera any time soon, it is getting busier.

Myth 3: Russia and China are ganging together to hoover up Arctic riches

China is so keen to make the most of the Arctic it has added a ‘Polar Silk Road’ to its ‘Belt and Road Initiative’, which aims to redevelop global transit for its goods. For, if the Northern Passage off Russia’s coast becomes free of ice in the summer months, Chinese cargo ships could reach Europe ten days faster than through the Suez Canal, and wouldn’t have to contend with pirates in the Indian Ocean.

-20-br.jpg)

China is currently building Arctic-ready super tankers and icebreakers, investing in the Yamal LNG terminal in Russia’s far North with technology from France’s Total oil and gas major, and even developing Arctic tourism. This is not simply a case of the geopolitical awkward squad sticking together, however. If Russia is a big part of Chinese plans, it’s because it owns the more accessible half of the Arctic coast.

The rising superpower is offering to invest all over the Artic. In Iceland, it has opened an observatory to study the Northern Lights, which the recently-bankrupted country could not have afforded otherwise. It has also helped Norway build the longest suspension bridge inside the Arctic Circle.

Chinese companies made a bid to build airports in Greenland that will boost the island’s economic viability, while pleasing the independence movement, but Denmark stepped in to win the contract to avoid upsetting the United States, whose military has a free hand over the territory by treaty. Some warn that China is setting debt-traps by tying small countries into too-good-to-be-true contracts.

-21-br.jpg)

Finnish projects are a good illustration of what is driving investment fever in the Arctic. Playing to its strengths in information technology, Finland is currently negotiating with Norway, Russia and China, amongst others, to lay a data cable under the Arctic ocean between Europe and Asia. The shorter route would reduce lag times and increase internet speed. There are also plans to build a railway between the Norwegian town of Kirkenes on the Arctic coast and Oulu, at the northernmost point of the Baltic. This would reduce shipping times for goods bound for Europe via the Northern Passage.

“It’s about trying to fix the problem of Finland being on the periphery,” according to Peter Vesterbacka, a former executive of the company that created the Angry Birds computer game, who is working to bring in Chinese investors to build a tunnel from Helsinki to Tallinn. “For Europe, we are on the edge, but if you look at this from a Eurasian or Arctic perspective, we are right there at the centre.” This vision of the Arctic as an opportunity for commerce and technology is what is driving the Arctic nations to work together, and with China. It’s also what is drawing other Asian and European players to the area.

Myth 4: Russia and NATO are heading for war in the Arctic

One key player has been conspicuously absent so far: the United States. It has never signed the UNCLOS and, thus, made no legal claims before the UN to the Arctic continental shelf. President Trump did open up most of Alaska’s outer continental shelf for oil drilling, but that does not entail grand transnational ventures.

Nevertheless, the US military, along with NATO, has started making noises about Russia’s resurgence in the region. At a Senate Committee meeting in March of 2018, Admiral Harry Harris of the Pacific Command worried about Russia developing air and naval bases on its northern Coast. “Russia is increasing its qualitative advantage in Arctic operations and its military bases will serve to reinforce Russia’s position with the threat of force,” he said.

NATO General Secretary Jens Stoltenberg has taken note of this as well, speculating that “increased Russian presence with modern military capabilities in the Arctic” will have “some consequences for the Arctic." Perhaps not coincidentally, in October-November 2018, NATO staged its largest military exercise in decades, simulating an invasion of Norway. Former Supreme Allied Commander, retired Admiral James Stavridis, admitted that the fictional attacker in Trident Juncture 18 was “clearly modelled on Russia.” So, does this mean NATO and Russia are indeed gearing up for war in the Arctic?

Probably not. A battle on the ice is highly unlikely because NATO countries don’t have icebreakers that can navigate the Arctic coast for most of the year. The United States Coast Guard has three, but only one is capable of operating in the Arctic. Britain has one, but it’s in the Antarctic. Norway has two. Russia, on the other hand, has at least forty, some of which are nuclear powered, and it’s building more.

NATO countries also have very few subs that can break through the heavy Arctic ice. While they can navigate beneath it and come out on the other side of the ocean, they aren’t up to sea battles or land invasions. On the other hand, Russia has been developing its fleet of submarines, some of which are already ice-capable. This could change, of course, but spending on Arctic military capabilities would have to become a budgetary priority and the spending would have to be sustained for many years. For the near future, this seems unlikely, as the Arctic isn't even mentioned in the United States 2018 National Defense Strategy Summary.

Why then is Russia fortifying its Arctic coast? The first reason is that North America lies on the other side of the still frozen ocean, and the quickest route for missiles, including nuclear ones, to reach Russia goes over the North Pole. As President Putin told the chiefs of the Russian Armed Forces in 2016, Russia should strive for strategic balance in order to preserve peace, and to be ready to effectively neutralise any threat to the country’s security.

The second reason is economic. As RIA Novosti journalist Irina Alksnis put it, “if you own something valuable, you must be able to defend it, otherwise it will be taken away from you.” A large proportion of Russia’s known and potential mineral wealth is located in the Arctic, including offshore.

Moreover, the Northern Passage which passes close to Russia’s coast, depending on the state of the ice, could well become one of the world’s key shipping routes.

Whereas the United States is trying to claim that the route lies in international waters, Russia is keen to retain control. Canada, which insists that the North West Passage winding through its northernmost islands and internal waters is subject to its exclusive jurisdiction, has found itself in a similar position, as the US likes to think of these waters as international too. Nevertheless, the fact the United States never ratified the UNCLOS weakens its position as a defender of the “rules-based international order” with respect to Arctic waters.

NATO Arctic countries often justify their suspicions about Russia’s motives in the North by referring to events in Ukraine. However, considering their praise of the cooperative approach of the Arctic Council, this alarmist rhetoric may well be serving other agendas, far from the ice.

The face of the region is undoubtedly changing shape as the icecap melts, but it is bringing activity rather than strife to its shores. We can only hope some of the ice will remain, and with it, native cultures, reindeer and a little of Santa’s magic.